By Rod Collins, Director of Innovation at Optimity Advisors and published in the Huffington Post

Enlivening Edge Magazine Editor’s Note: Over the years since 2016 when this article was written and then republished by us, it has become one of our go-to references when we are asked for a good, accurate, brief desciption of the Reinventing Organizations model. Another good reference is this one. The one below is relatively long but one of the best introductions around.

Thanks to the Internet, there’s a new worldview, and it is revolutionizing the way we build organizations. According to Frederic Laloux, the author of Reinventing Organizations: A Guide for Creating Organizations Inspired by the Next Stage of Human Consciousness, the days of the top-down hierarchy as the dominant organizational framework are numbered. Despite its continued preference by the current power elite, the bureaucratic management model is rapidly becoming both limited and obsolete now that the technology revolution has spawned a major inflection point in human history by unleashing the extraordinary and unstoppable phenomenon of distributed intelligence.

According to Laloux, organizations are expressions of the dominant worldviews of their times. His extensive research traces the evolution of organizations over the past 10,000 years. Over that period, Laloux noticed whenever we change the fundamental way we think about the world, we come up with new and more powerful types of organizations, and while prior forms of organizations don’t completely disappear, the higher order organizational frameworks that evolve from new ways of thinking tend to become the dominant practice of the new age. Laloux also noticed that these passages from one age to another are not continuous gradual transitions, but rather sudden transformations—and, most importantly, we are in the midst of one of these transformations right now.

Color-Coded Typology

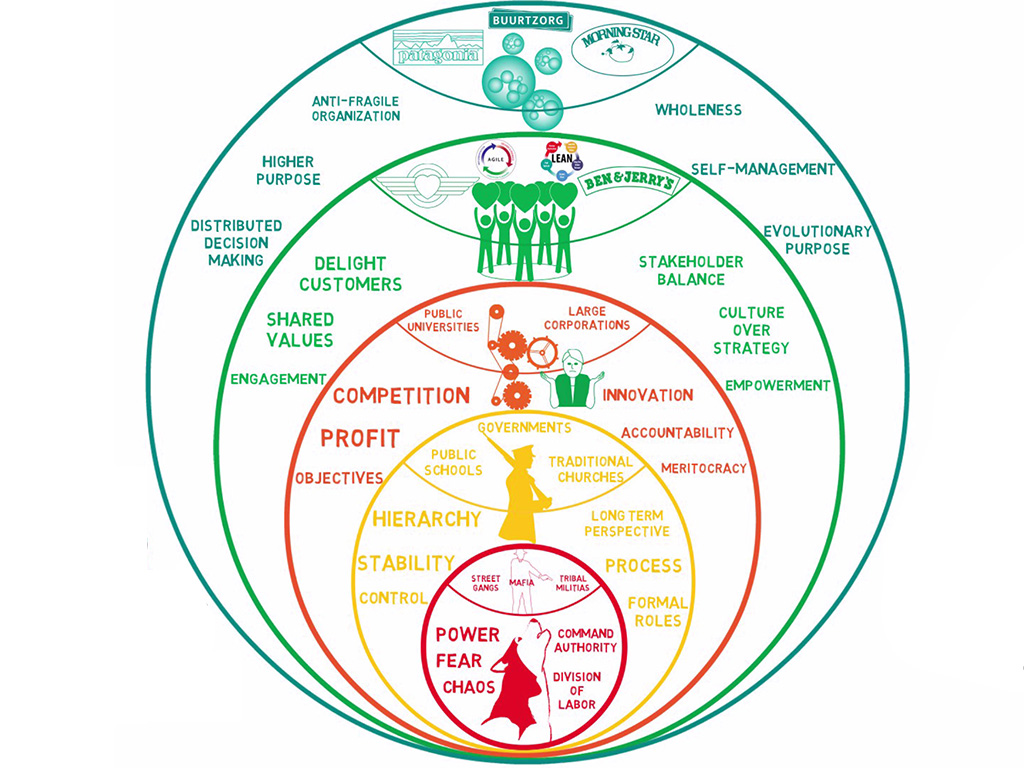

Using a color-coded typology inspired by the work of Clare Graves, and made popular by Don Beck and Christopher Cowan in their book Spiral Dynamics, Laloux outlines the evolution of four types of organizations over the last ten millennia and describes in detail the attributes and characteristics of a fifth and radically different emerging new organizational form.

The four historical types are:

- Red: The first forms of organizational life appeared about 10,000 years ago when people were organized into chiefdoms. The fundamental rubric in these small groups is the exercise of overwhelming personal power through fear or submission to keep organizations intact. This type of organization is highly reactive and focused on the short-term. Current examples of Red organizations include the Mafia, street gangs, and tribal militias.

- Amber: Organizational life dramatically shifted when the agricultural revolution transformed nomadic hunter-gatherers into settled farmers and gave rise to the first bureaucracies with the emergence of political states, social institutions, and organized religions. Authority is linked to formal roles rather than to powerful personalities. These roles are arrayed in strict chains of command to direct all aspects of social activity. The organizational breakthrough of bureaucracy, at the time of its emergence, is its capacity for long-term planning and scalability, which enables the accomplishment of complicated endeavors. Current examples, according to Laloux, include the Catholic Church, the military, and most government agencies.

- Orange: The next evolution in organizational life is generated by the industrial revolution. While Orange organizations retain the hierarchical pyramid as their basic structure, followers are given more autonomy in how to accomplish management directives Nevertheless, consistent with the industrial worldview, organizations are viewed as machines that need to be manipulated and controlled by their leaders. Thus, these organizations can feel lifeless and soulless despite the small freedom workers have in performing their tasks. The multinational company is a current example of an Orange organization.

- Green: This next organizational iteration is a response to the shadow side of the Orange organization. With the increased educational level of the workers, especially in the second half of the twentieth century, organizational leaders became uneasy with the exercise of hierarchical power. Thus, Green organizations emphasize the importance of empowerment, striving for bottom-up processes, gathering input from all, and building consensus. However, despite its focus on creating strong human cultures, Green organizations are still hierarchies because the notion of empowerment is predicated on the premise that the leaders have the authority to choose whether or not to delegate their power. As long as the leaders choose to delegate, they remain Green; but if a new leader comes along who doesn’t care about culture, these organizations can quickly morph back to Orange. Laloux cites Southwest Airlines, Ben & Jerry’s, and DaVita as current examples of Green companies.

The Teal Organization

Over the course of civilized history, the four historical models have had one common feature: bosses. From the first chiefs to present day CEO’s, the exercise of power has been about “being in charge.”

Most of us cannot conceive how organizations would work if no one was in charge, which is why every one of the four historical models is some form of a top-down hierarchy.

Even in the empowerment structures of Green organizations, the people in charge have to delegate their power for empowerment to take hold.

But, Laloux asks, “What if we could create organizational structures that didn’t need empowerment because, by design, everybody was powerful and no one was powerless?” In other words, what if we could create organizations where power wasn’t a function of being in charge, and thus, there were no bosses? The answer, according to Laloux, is the Teal organization.

The Teal organization is a revolutionary new management model that operates from the premise that organizations should be viewed as living organisms, and therefore, function more like complex adaptive systems than machines. Accordingly, this organizational form is a structure of flexible and fluid peer relationships in which work is accomplished through self-managed teams. In Teal organizations, there are no layers of middle management, very little staff, and very few rules or control mechanisms. Instead of reporting to single supervisors, people are accountable to the members of their teams for accomplishing self-organized collective goals. As counterintuitive as it may seem, the elimination of controlling bosses typically enables a better controlled organization because, Laloux points out, “peer pressure regulates the system better than hierarchy ever could.”

Everyone’s a Manager

While there are no bosses in Teal organizations, these are not leaderless enterprises. In fact, Teal organizations actually have more leaders than their hierarchical counterparts, as Gary Hamel, the management guru, discovered when he visited Morning Star, the world’s largest tomato processor and one of the bossless organizations in Laloux’s research. After touring its main facility and becoming familiar with Morning Star’s unconventional organizational practices, Hamel commented to Chris Rufer, the company’s founder, that the innovative company had discovered how to manage without managers.

Rufer saw it differently and pointed out that at Morning Star everyone is a manager because everyone is responsible for the resources needed to get the job done and for holding colleagues accountable for accomplishing the company’s mission.

All Voices Count

The leadership difference between Morning Star and the traditional company is the defining distinction that enables self-organized peer-to-peer networks to be far more efficient in solving complex problems than multi-layered top-down hierarchies. In hierarchical organizations, leadership is a fixed role and decision-making authority is ascribed to a limited number of key individuals in the formal chain of command. Thus, traditional organizations are designed to align their resources and to solve their day-to-day problems by leveraging the individual intelligence of their brightest or most experienced people. In the hierarchical model, the voices at the top count more, and in many instances, the voices at the bottom don’t count at all, which may explain why workplace surveys continually find less than 30 percent of workers feeling engaged at work.

In self-organized peer-to-peer networks, all voices count because anyone is capable of sensing a problem or an opportunity. And since everyone is expected to be a leader, everyone has the wherewithal to recruit followers to determine whether or not action needs to be taken. If enough people join up, action is taken; if recruits can’t be found, nothing is done. What makes well-designed peer-to-peer networks so efficient, when compared to top-down hierarchies, is their inherent ability to leverage their collective intelligence as a powerful resource for responding to fast changing circumstances.

A Major Inflection Point

In a relatively stable world where all social institutions share the same hierarchical paradigm, leveraging the individual intelligence of the few is a workable premise for designing organizations. For more than 10,000 years, there was no practical competition for the top-down hierarchical paradigm and no incentive to change for those who enjoyed the lucrative benefits of being on the top of these pyramids. But that is all changing, because thanks to the recent rapid emergence of the digital revolution, we are in the midst of a major inflection point that is literally changing all the rules for how the world works and transforming the world into a hyper-connective network with the ubiquitous capacity to leverage the power of collective intelligence.

In next month’s blog, we will explore this inflection point and its revolutionary new organizational model in deeper detail. But, in the meantime, consider this question: What color is your organization? [EEMagazine Editor’s Note: Part 2 was apparently never published.]

Really like this as a clear and accessible introduction to the ideas. I will be sharing it a lot!