By Ted Rau for Enlivening Edge Magazine

Every organization evolves on several levels.

- On the team level — what needs to be done, and who does what?

- On the operational level — what lives in what circle?

- On the organizational level — what is our organization about?

- On the ecosystems level —all of an organization’s relationships to the outside: new partnerships, new suppliers, and shifts in our stakeholders.

How can we design those levels to make sure the organization can respond quickly and appropriately to changes on all of those levels?

Team level — roles

Roles are fine-grained jobs

On the team level, we need to figure out who is doing what. The easiest way is to have defined roles in each domain. Roles are different from jobs or positions. With roles, we can have a more fine-grained approach to the work. Each cluster of tasks and responsibilities gets a “box”, the role, and each person will hold several roles. For example, the same person might oversee shipping of products as well as having a role in Marketing.

The nice thing for role-holders is that everyone can assemble a portfolio of roles that suit their needs, in terms of the nature of the work and the workload.

It also makes it easier to shift and create roles. Whenever we want to make a change, we simply write or review a role description (with the level of detail we’re comfortable with) and approve it by the team. Then we fill the role until we revisit it at a given date in the future to see what needs tweaking and improving.

The catch-all function

Now, what happens if there’s something that needs to be done that isn’t already covered in a role? The first question is always: is it in our domain? Or does this live in another circle (aka team)?

If we decide it is in the circle’s domain, that’s where the leader of the circle comes in. If a task doesn’t get done by anyone, the leader will surface that and bring it up so it can be filled. If time is pressing, the leader will have to do it themselves or ask someone to fill in until a “home” is found for the tasks.

As a leader, I take time to think about the circles I’m leading to ask myself: what is falling through the cracks? By initiating that conversation, we can be more adaptive as a team.

Summary

(a) We need defined domains to know where the conversation about finding a home for this task needs to happen.

(b) And we need a leader function to make sure someone can distribute stray tasks.

Operational level

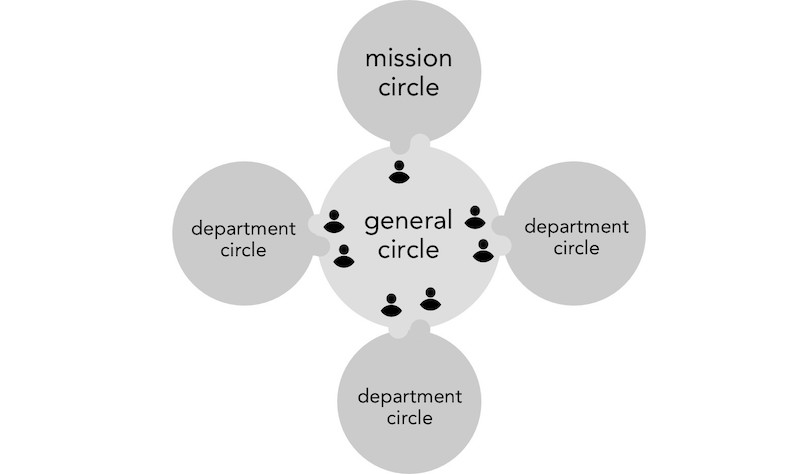

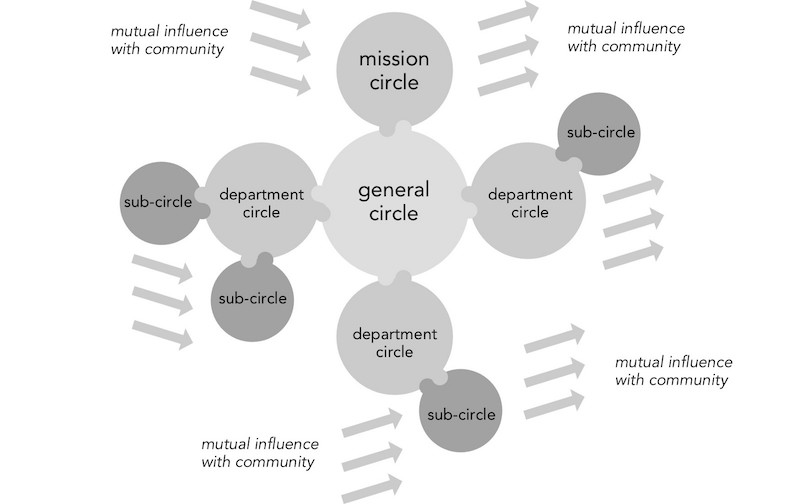

On the operational level, things look very similar. In role-based/circle-based systems (sociocracy originally, but also other systems like Holacracy®), all roles and operations that live in a domain are held in a circle.

But who defines the domains? And what if we need to make a change to a domain? Changes in domains aren’t uncommon at all — quite the opposite, they are signs of a living, adapting organization. Domains might need tweaking as we clarify responsibilities or as we shift priorities and handoffs from one team to another.

For example, it might be that our fundraising team might actually be better off being connected to our social media team than our finance team. Our organizational structure should follow our operations, not vice versa.

Any adaptive organization needs to be able to make these changes, and there’s an easy, resilient way of doing that: by defining that each circle’s domain gets defined in mutual consent with its parent circle. That way, our structure always offers us a place to make changes.

A catch-all

The General Circle also offers a catch-all. Between the roles of a circle, the leader makes sure the unassigned tasks find a home. Between the circles, the General Circle makes sure all unassigned domains find a home.

For example, if an organization wants to add grant writing to its activities, there might not be a circle that is already associated with that topic. We can avoid a situation where people just point fingers, or where a decision is made top-down. If grant writing is not an obvious fit in an existing circle – and it can be added by consent there – then the General Circle will take the topic and make sure it finds a home.

Summary

(a) With defined domains, we can empower teams to self-organize in a specific area.

(b) If there are gaps in the domains, the General Circle closes them.

Image from Many Voices One Song. Sharing power with sociocracy (2018)

Organizational level

Organizations change as well

Does it ever happen that an organization changes not only who is in charge of what, but even what the organization’s purpose is overall?

This might not be as frequent, but any organization needs to be able to update or adapt its overall aim and purpose or mission. Things change internally and externally, and organizations that don’t adapt to that will wither and die.

Having a purpose is not enough. Being able to have and change the purpose is what helps create an adaptive organization and is also essential for a resilient organization.

Changing the purpose in a self-organized context

In a top-down hierarchy, the top defines the purpose. How can it work in a self-organized and/or decentralized situation?

Let me first speak to how it doesn’t work, at least quite often. Many groups have the impulse to want to include every member of the organization when we change the purpose. And while I agree that every member should be heard on those decisions, I’ve seen it fail often enough to say: I don’t recommend it. It leads to endless internal friction, splits of organizations, and lots of heartache and frustration.

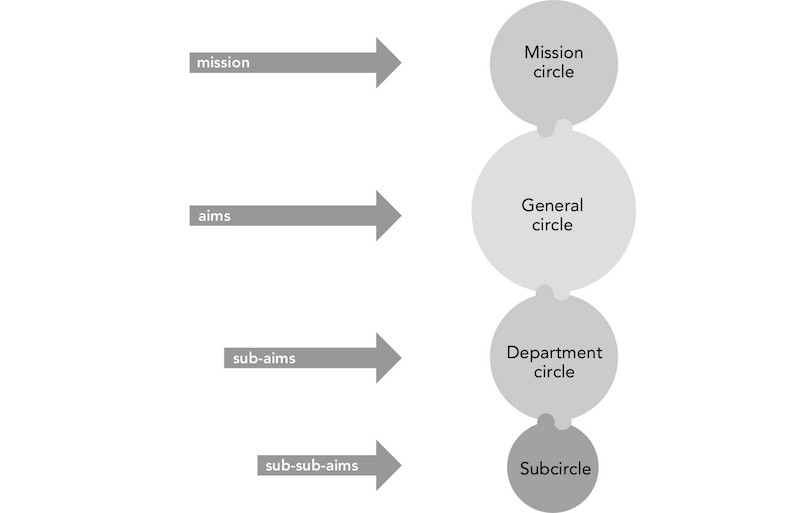

Just like any other decision, this decision needs to have a place where it can be resolved, and the most promising place for it is what we call the Mission Circle — often, that’s the board, an advisory board, or similar circles.

To retain our agency as an organization, we have to empower that group to make changes to the aim and purpose. Therefore, the domain of the Mission Circle is the organizational aim and mission (or purpose).

Image from Many Voices One Song. Sharing power with sociocracy (2018)

I’ve witnessed organizations that couldn’t update or even negotiate their organizational aim, leading to serious implications. These were somewhat autonomous organizations that were connected to a Global organization, creating a lack of clarity. Who gets to define the organizational aim, the global organization or the local chapter? In one specific case, without a place to make the decision, they argued. Last I heard, half of the key members have left the organization in frustration.

Again, a good and responsible Mission Circle will include other members in the conversation, but they are and need to be the hosts for this conversation and those who can sign off on the decision, so change is possible, and we don’t get stuck.

Summary

There needs to be a place where, with appropriate feedback from others, a decision on the organizational-level purpose or aim can be made.

Ecosystemic level

Every organization holds a lot of expertise — in its operations and internal processes. Yet, every organization will also have blind spots. There will always be things that an organization cannot see — because we have assumptions we don’t question, things we do not know, and perspectives we have never seen.

And, of course, we have no way of knowing when there’s something we don’t know.

Now what?

The solution I’m offering will not be an all-sufficient solution; it needs to be combined with other solutions. But it’s an excellent start. Every organization can be connected to the outside by having several non-members inside as decision-makers (or at least as input-givers).

This requires trust — but trust is possible when our decision-making method is consent. (And not, for example, majority vote, where external people might outnumber the internal people.)

The place for those external members is not in the operations — they’d think like the insiders soon. A suitable place is in the Mission Circle, where we discuss how the organization relates to the world, and its purpose.

A great moment where I noticed how this makes our own organization more adaptive was when an outside member on our own mission circle gave feedback to our budget and said: “This budget does not really reflect the priorities that you have been talking about.” I realized instantly that he was right. All the insiders, including myself, had been in groupthink mode.

In my practice, I see way too many organizations that don’t include outside voices at all, and that’s risky. Every organization without significant outside influence will go stale in the long run. Invite and welcome those outsiders and give them a place where they can share their valuable perspectives and it can flow into the operational level of the organization. (Ideally, your own members are also encouraged to be that external person somewhere else.)

Image from Many Voices One Song. Sharing power with sociocracy (2018)

Closing words

The basic design principles of systems like sociocracy are always the same:

Everything needs to have a place where it can be decided. That means we need:

- clarity on who decides what & trust that a small group of people can be empowered to make important decisions

- To resolve issues and fill gaps, we need a “superordinate” place where that clarity can be created. In sociocracy, that’s built into the nested structure.

With these principles — whether you choose to use sociocracy’s concrete implementations or not —you can make the difference between internal drama and endless discussions or an adaptive, evolving, resilient organization.

Ted is an advocate, trainer and consultant for self-governance with a main focus of sociocracy. After his PhD in linguistics in Germany and work in Academia, he co-founded the member organization Sociocracy For All and spends his days consulting, teaching and leading the member organization as Executive Director.

Ted is an advocate, trainer and consultant for self-governance with a main focus of sociocracy. After his PhD in linguistics in Germany and work in Academia, he co-founded the member organization Sociocracy For All and spends his days consulting, teaching and leading the member organization as Executive Director.