By Lisa Gill and Nick Parker for Enlivening Edge

UK-based manufacturing company Matt Black Systems has been operating as a self-managing company for fifteen years. The shift from hierarchy to their unique self-management model resulted in a 300% productivity boost. In Part 3 of this Enlivening Edge series (see Part 1 and Part 2), we discover the underlying principles of this system.

CEO Julian Wilson said when he imagined “super productivity,” he pictured a scene from Charlie Chaplin’s “Modern Times”: factory workers’ hands moving faster and faster on the production line. Yet when you walk the factory floor at Matt Black Systems, it’s eerily calm. The project managers (so-called for lack of a better, externally-recognised job title that describes the many hats they wear) perform multiple roles, from sales to design to manufacture to control, and yet there is no manic activity. They are relaxed and happy to chat with visitors in their surprisingly tidy and ordered workspaces.

When I first encountered Matt Black Systems, it was on the Reinventing Organisations Discourse discussion forum and Julian was sharing their “fractal system” (inspired by how nature efficiently uses repeated patterns at different scales driven by a single rule set.) To create this system, Julian and his business partner Andrew Holm broke down all the necessary organisational constraints (e.g., legal or regulatory constraints) into more than 220 “recipes” in order to devolve them into the organisation (as opposed to dividing them across a hierarchy or separate departments.) These were then built into a bespoke IT system to automate administrative tasks for employees and also devolve fiduciary constraints from the directors to every individual. In essence, this means that every project manager in Matt Black Systems is totally responsible to the law and stakeholders, and responsible for their decisions and resources.

My first reaction to this was: it feels very inhuman and mechanical. But when I chat with Julian, he is very passionate about the humanity in the Matt Black Systems model. Just as Julian is a powerful combination of his training as both an engineer and a psychologist, there is a paradox of humanity in this self-management model. He described it to me using the analogy of a virtuoso violinist who is able to express their humanity through an inanimate object (their violin) and sheet music (someone else’s composition.) The violin is just a technical tool but one that is beautifully designed to accommodate the humanity of the performer. In the same way, project managers at Matt Black Systems operate within very clear organisational constraints and yet have huge amounts of autonomy and freedom to express themselves. The organisation’s constraints are specifically designed to accommodate their humanity.

Julian believes that most organisations start with the best intentions but when an employee is not achieving the desired performance, management reacts by doing something to them – training them, introducing new and more prescriptive policies or processes, or reprimanding them in pursuit of a more predictable result.

People bring instability which leads to constraining, restricting systems and processes that try to restore stability but in doing so, employees can no longer express their humanity. As Julian explains, “it would be like reacting to a violinist messing up a note by replacing his instrument with an iPod playing violin music!” Over time, the ability of the employee to express themselves is diminished in the search for greater predictability and consistency – the good is thrown out with the bad.

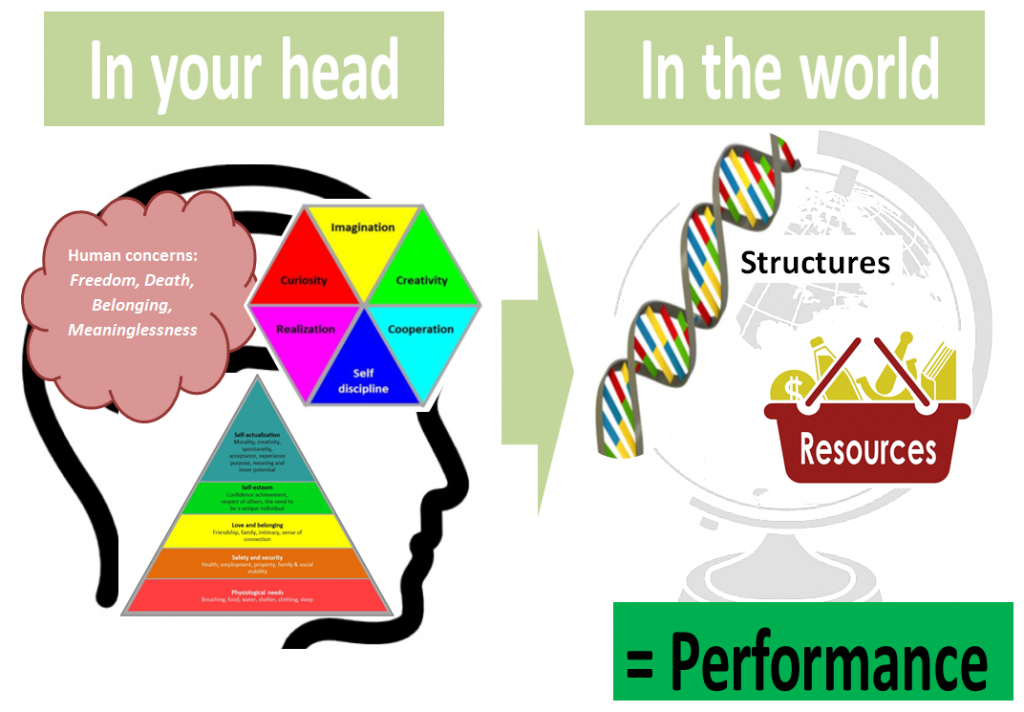

The above is a diagram Julian uses to explain the Matt Black Systems model. On the left are elements ‘in your head’: your needs, concerns, and skills. These are the things that make us human – machines don’t have them. The six key skills human beings bring are: curiosity, imagination, creativity, cooperation, self-discipline, and realisation. He argues that most companies try to interfere with these inner elements, thus activating these human concerns (Am I performing well enough? Will I be fired? Do I belong?) and causing them to withdraw many of their qualities (for example, if I am micromanaged, I don’t get the opportunity to use my curiosity or creativity so I might react by withdrawing my self-discipline or realisation almost as punishment for not feeling valued.)

At Matt Black Systems, Julian and Andrew realised their model should manipulate only the ‘in the world’ parts – activities (sales, design, manufacture, control) and measures (quality, delivery, profit, compliance). The primary role of organisations, Julian says, is to set the structures to get the best from what they’ve got and not to delve into a person’s head. Matt Black Systems’ fractal IT software doesn’t tell people how to perform these activities; it simply tells them records need to be kept and provides an easy way for them to do this. It’s the equivalent of providing sheet music and a well-made instrument – how they play is up to them.

But how did the project managers experience it? To go from working in a hierarchy to suddenly being responsible for 220 plus ‘recipes’ must have been unsettling, right? Nick posed this question to Ivan, one of the team who had been at Matt Black System throughout the shift to self-management. He replied very casually, “not really.”

He explained that each new responsibility was introduced gradually so it never felt overwhelming. In reality, they only use about 15% of the 220 plus recipes on a day-to-day basis; many of them are for exceptional circumstances. And even though he saw some colleagues protest and leave during the transitional phase, Ivan saw the changes as another opportunity to learn, take on more responsibility, gain more freedom and, of course, earn a little more.

When we met him, Ivan had just returned from a month-long holiday in Colombia to visit family. There is no fixed holiday allowance and there are no set working hours at Matt Black Systems. Each project manager has a buddy, and if they want to take some leave, it’s their responsibility to hand over their work and customers properly. In terms of the “wholeness” component of Frederic Laloux’s Teal worldview, project managers are free to leave in the middle of the day to spend time with their children, for example, and come back to the office later when they choose.

When we asked Ivan how they make sure people don’t abuse the system, he replied, “Well, there’s taking freedom, and then there’s taking liberties! You notice if someone hardly ever shows up to work; you can’t really hide here.” Project managers also process their own pay raises. They simply fill in a form (again, not as permission, just as a record of the change they’re making to their contract) which justifies the pay raise based on increased sales – and it’s theirs.

On our visit, we heard two stories that demonstrated just how powerful self-management can be. The first was a story about a gutter becoming blocked. Alex, another project manager, told us that the guys got together one lunch break to discuss what to do. Sure, they could contribute to the cost and hire a contractor, but that would come out of their profit.* As some of them had some free time on Friday afternoon, they worked out that it would be cheaper to hire the equipment and simply unblock the gutter themselves. So that’s what they did, without having to ask for permission or notify management.

Given that each individual is a virtual business unit of one and so their operations are relatively isolated from each other, this is a great example of how cooperation happens at Matt Black Systems. In part they cooperate because it’s in their best interest: if they need to enlist a colleague to support them on a particularly big project or they’re struggling financially one month and need to ask for help, it’s beneficial to have good working relationships. Economically it makes sense to coordinate stock orders, too, with one project manager acting as the ‘bulk breaker’ to the others. But there is also a distinctly collegial atmosphere. Each employee could tell us who they’d go to for particular expertise; there is a healthy level of banter and competition, and we heard how they were able to be straight with each other in team meetings.

The second story also highlights one of the challenges for founders or CEO’s in self-managing organisations: the temptation to be a heroic leader in a crisis. One night, in a neighbouring factory, a disgruntled employee broke in and started a fire. Having disabled the fire alarm in his building, it was only when Matt Black Systems’ alarm went off that the fire brigade arrived. It took them a while to work out that the fire was coming from the building next door and not their factory, but the damage was done.

Julian remembers standing outside in the car park with the team in the early hours of the morning in silent despair. Triggered by stress, his old management habits surfaced. He had an impulse to take control and rescue the situation. He addressed the team and started to formulate an action plan when suddenly, one of the project managers interrupted. “We’ve got it under control, Julian, it’s fine. You take care of the insurance company, and we’ll do the rest.” The team sprang into action, organising the repairs and handling customers to ensure operations continued as smoothly as possible. Julian sees it now as one of the pivotal moments in the company’s history.

It was a strange realisation – to feel both proud of the people and the success of the system and yet to have confirmation of how unnecessary he was. It also demonstrates that the command-and-control urges are never far below the surface and how we must always be on guard against them reasserting themselves in our thoughts and actions.

Andrew never visits the factory floor for precisely this reason – the temptation for project managers to ask for his opinion is too great and therefore his very presence threatens the self-managing ecosystem. Both Julian and Andrew coach the project managers regularly offsite, but only to pose questions and to play back what they’ve heard, so that the responsibility for the work or the problem still sits with the coachee.

Matt Black Systems’ experiment has paid off and today the system works incredibly efficiently. Of the 30 original employees before the shift to self-management, there are just 12 left today, yet turnover and profit have risen and purchases have fallen. So whilst this shows impressive results, it also reinforces a common theme in these progressive organisations: self-management isn’t for everyone. People in management roles before the transition were given the opportunity to stay on the same pay, but the prospect of losing their status was too difficult and they all ended up leaving – many to pursue totally different careers, somewhat tellingly.

Those who have thrived in the new self-managing model, interestingly enough, are mostly people who had little or no workplace experience prior to joining. Perhaps the lack of hierarchical conditioning made it easier for them to embrace this way of working. Julian says Matt Black Systems is for self-directed people who want to co-create and collaborate using novel structures, though it does trouble him that the model is in danger of being somewhat exclusive.

All of the project managers we spoke to describe the Matt Black Systems working environment as tougher, but more fun and more rewarding. And all of them told us they could never go back to an ordinary workplace now; they wouldn’t be able to tolerate the lack of freedom. The more I’ve spoken to Julian and others about the Matt Black Systems model, the more I realise that the principles are fundamentally simple: do whatever you like, as long as you don’t break the law. The interests of the company, the individual and the customer are all fully aligned in the structure so those parts pretty much take care of themselves. Like Buurtzorg, their software plays a crucial role in supporting the system. But the automation is really just about freeing up the humans from the chore of recordkeeping and to allow them to focus on bringing those six key skills (curiosity, imagination, creativity, cooperation, self-discipline and realisation) to the table.

Matt Black Systems reminds me of the acclaimed conductorless chamber orchestra, Orpheus, founded by another Julian (Julian Fifer) in 1972. He once said in a New York Times piece:

Orpheus is the particular blend of freedom and responsibility that goes with working as a chamber orchestra without a conductor.”

And that’s exactly what Julian and Andrew have created at Matt Black Systems: a particular blend of freedom and responsibility that produces extraordinary results. Orpheus’ founder named the orchestra after the Greek god who created music so powerful that stones rose up and followed him. My hope is that Matt Black Systems will inspire other leaders to rise up and experiment, creating their own particular blends of freedom and responsibility that enable people to work wonders.

—

*Each project manager splits their profit five ways: 20% to the two directors, 20% to tax, 20% into a personal investment pot to deploy as they see fit, 20% is take-home profit, and 20% goes into a collective investment pot.

Nick Parker is currently exploring how the principles of self management might be effectively employed in the public sector in the UK. For the past 15 years he has worked at the leading edge of organisational change within that sector. He holds the national portfolio on reform in the sector for the RSA Fellowship.

Nick Parker is currently exploring how the principles of self management might be effectively employed in the public sector in the UK. For the past 15 years he has worked at the leading edge of organisational change within that sector. He holds the national portfolio on reform in the sector for the RSA Fellowship.