A Conversation with Dr Margaret Hannah by Anna Betz for Enlivening Edge Magazine

‘Humanising Healthcare’ – Part 2: Doing What Matters and Mobilising around a Purpose is here.

A: I felt very inspired by reading your book Humanising Healthcare. I also know of your work with the International futures Forum (IFF) which is very systemic in its approach to healthcare. As the newly appointed Director of Public Health for National Health Service Fife (UK) since November 2015, what have you actually been able to achieve in relation to your vision and your systemic approach?

A: I felt very inspired by reading your book Humanising Healthcare. I also know of your work with the International futures Forum (IFF) which is very systemic in its approach to healthcare. As the newly appointed Director of Public Health for National Health Service Fife (UK) since November 2015, what have you actually been able to achieve in relation to your vision and your systemic approach?

M: In practical terms there is a lot of learning you have to do when you take on a role like this. It is like going on a roundabout really really fast. You just jump on. It’s about finding yourself in a different landscape, in a different environment to the one you have been in.

In the first year I was really just trying to understand how things worked at that level given that all health boards and the NHS are under such strain at the moment. I found myself in the firing line for finding savings. We had a lot of internal discussion around all of that.

The appointment was like a baptism with fire. I wouldn’t suggest that I moved much along in that first year although I wouldn’t like to disparage what I did do. It is important to remember that if you are going to think systemically and act systemically, you need to understand where you are in the system.

It took a bit of getting used to. It is about understanding the constraints but also the opportunities that a position might give you. In terms of opportunities, being aware of the innovative work that is going on in Fife helped me to continue in the face of that difficult environment. I am giving the innovative work recognition, credibility, and some level of protection to help it grow.

A: It seems that you could see the future as already being present in the innovations you saw happening. Thanks to your position you could give them recognition, credibility, and protection. That is really wonderful.

M: I have changed a lot in that role and became a much more ‘both-and’ person.

It is not about making people wrong in what they are doing but acknowledging what they are doing right given their circumstances, and offering them an ‘and’. I don’t have to break everything down into detail. People in organisations have very little time anyway. It is very hard for people in organisations to take in something that is quite different. On the other hand they are happy for me to come along and do it, even knowing that it is quite different; they trust it will take root and flourish.

A: If they are happy for you to carry on, I would imagine that requires trust. What gives them this trust in you to allow you to get on with it?

M: First and foremost you have to deliver on what you are required to do by the organisation.

So I have to absolutely deliver safe health protection. In Scotland, health protection, resilience, and health service work are still integrated. Our department is responsible for all of that, and I have to show that I run a good safe ship. That is what earns the trust.

I have to be a constructive colleague in the senior team, help out with their struggles, and take on tasks if necessary that then might lend themselves for this further development.

A: What kinds of tasks have you taken on?

M: I have taken a more active role in staff health compared to my predecessors. I take the view that Public Health needs to look after staff health because without the staff, the health service falls apart, and a lot of people’s health gets damaged. The work I have been doing around humanising healthcare is playing into that whole area. Not to step on anyone’s toes, but it just adds to the mix.

A: What you are describing seems an important aspect of transformational leadership. You put things in place which enable systems to shift and you know when to step out of the way. What you are doing seems about principles that other leaders within the system could learn from, not by learning a new method or using another tool but by reflecting themselves on what qualities they need to develop.

M: I would add two other ingredients to the mix.

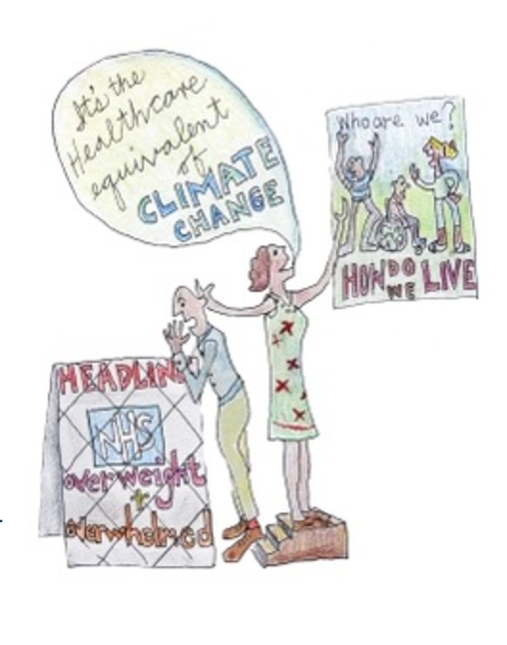

- The first would be that insight trumps strategy. There is a lot of talk about the importance of strategic plans, a clear vision, and a clear plan, which is all true. However, for me, at a deeper level anything you write on paper or anything you put out in a consultation document is framed by a certain set of assumptions. It is those very assumptions that need to be questioned now.

For transformative change, you have to change the underlying assumptions.

Before you can express something as a refreshed argument, strategy or plan, before you can present a level of detail, you have an insight. That insight for me is written in Humanising Healthcare.

It is the shift from that clinical gaze to a person-centred one. It is the relational piece and it is emphatically person-centred. It is emphatically about what matters to you. Once we know what’s wrong with them, once they know what’s wrong with them, then it’s a question of ‘what matters to you?’ That insight is what is fueling the whole way in which I work and it has been doing that for the last 6-7 years.

- The second ingredient is to develop your own practice. To see that your role isn’t about position; it isn’t about a job title; it isn’t about executive powers as such. It is about your own practice.

I happen to be in public health, so my practice is oriented towards the health of the population. But it’s done on the basis of ‘I do my own reflection, my own meditation in the morning; I do my own nourishing of my health and wellbeing; that is a practice along with promoting it with others.’ It is about being the model not just in yourself personally but in the relationships you have around you. And it’s a matter of the kind of culture that you are trying to foster. We are all practitioners today.

A: How do you keep those aspects alive in you when you are under pressure?

A: How do you keep those aspects alive in you when you are under pressure?

M: You have to design it into the pattern of your life, design in opportunities to reflect and learn. And that is true of projects as well. We have annual learning events. There is a reflective practice element to people working in this way.

We have worked with researchers, improvement science people, to try and get to the point where we can start to measure the impacts. We are not quite there yet in terms of your traditional forms of measurements. But that is a necessary part of it. We are having to learn how to do that as well.

Meanwhile we are very hungry for the staff stories, of what happens when they work in this way.

I had a story from a physiotherapist today about a man she saw. He has been using a mobility scooter for a long time and was very low in mood, not doing very well. It turned out that when she asked him “So what matters to you?” she found out he had been a dog trainer. He still had 2 dogs. When it became clear that what mattered to him was to walk his dogs, she put him in touch with the local leisure centre which runs exercise classes. He kept in touch with her, and four months later he is walking 4 miles a day with his dogs.

When she suggested to him to go to the leisure centre and tell others how he had done this, he said, “I don’t need to tell them. They just need to have conversations with you like the one you had with me.”

That was for her the most powerful example of this approach. It is inspiring for all of us to hear those kinds of stories. That sort of feedback is what keeps me going really.

[i] AB: This is because modern medicine is designed more for acute problems, surgical interventions and drugs. It is quite good at controlling symptoms and/or killing microbes. It is looking at the person from a clinical perspective. Chronic problems on the other hand typically benefit from a more holistic and person-centred approach which is why people need to be asked what is important to them. Healing a chronic problem needs the cooperation of the patient which is why it is important to work in a person-centred way.

Margaret Hannah is Director of Public Health for NHS Fife, Scotland. She studied medicine at Cambridge University and St Thomas’ Hospital, London and later trained in public health in Hong Kong and London. Margaret has pioneered fresh thinking in public health and the culture of healthcare. She was part of a five-year enquiry into culture and wellbeing which in 2012 culminated in the publication of The Future Public Health (Open University Press). In 2014, she published ‘Humanising Healthcare: Patterns of Hope for a System under Strain (Triarchy Press)’. In addition to her role in Fife, Dr Hannah is a visiting professor at Robert Gordon University and a Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians.

Margaret Hannah is Director of Public Health for NHS Fife, Scotland. She studied medicine at Cambridge University and St Thomas’ Hospital, London and later trained in public health in Hong Kong and London. Margaret has pioneered fresh thinking in public health and the culture of healthcare. She was part of a five-year enquiry into culture and wellbeing which in 2012 culminated in the publication of The Future Public Health (Open University Press). In 2014, she published ‘Humanising Healthcare: Patterns of Hope for a System under Strain (Triarchy Press)’. In addition to her role in Fife, Dr Hannah is a visiting professor at Robert Gordon University and a Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians.

Anna’s background is in Health and Social Care with training in Herbal Medicine, Socialwork, Mindfulness Practice, Transparent Communication, and Systemic Family Therapy. She practices a pro-active evolutionary approach to Health and Wellbeing and leads on projects in the UK National Health Service using Mindfulness and diet for people suffering from chronic inflammatory diseases like diabetes and dementia. Her passion for building thriving and sustainable communities inspired her to co-found the HealthCommonsHub. She feels at home in places where individual, communal, organisational, and social evolution meet, and where people support each other in becoming whole and feel enlivened.

Anna’s background is in Health and Social Care with training in Herbal Medicine, Socialwork, Mindfulness Practice, Transparent Communication, and Systemic Family Therapy. She practices a pro-active evolutionary approach to Health and Wellbeing and leads on projects in the UK National Health Service using Mindfulness and diet for people suffering from chronic inflammatory diseases like diabetes and dementia. Her passion for building thriving and sustainable communities inspired her to co-found the HealthCommonsHub. She feels at home in places where individual, communal, organisational, and social evolution meet, and where people support each other in becoming whole and feel enlivened.