By Dick Baker for Enlivening Edge Magazine

What would organisational ownership and governance look like if they were designed to enable the evolution of next-stage organisations? As organisations evolve we can see that while current model of ownership and governance allow evolution, my question is whether they are actively supporting this evolution.

To provide a supportive foundation for next stage organisations I believe we need to attend to ownership and governance arrangements. The cultural narrative of company ownership has been distorted to such an extent that in this first article I describe how we have come to where we are today, and uncover a few important myths, before the second article in which I will explore into the future.

Jon Freeman wrote an article (EE Magazine Issue 7) on Ownership, Stewardship, and the Planetary Commons which explores wider ownership issues in the context of reinventing capitalism, and as he points out “no one has yet designed a means by which we transition”. In these articles, I focus on practical next steps for the transition of ownership and governance.

As we journey towards purposeful business and on to evolutionary purpose, both ownership and governance will be different from what is common today. In many businesses traditionally the directors and the Board of Directors are seen as the pinnacle of power and control, the focal point between external accountability (to the ownership) and internal structures, processes and people. In a Teal-consciousness world, not only will the role of directors and the idea of ownership evolve, but perhaps also the company form itself.

Ownership is an area of next-stage organisations that has had less attention than some other areas, and given the damaging myths described below, it is one I’d like to explore.

A brief history of company ownership

While the history of companies goes back a long-time, incorporation was set out in England in the early 17th century. The famous East India Company received its Royal Charter in 1600 as a joint-stock company. Never-the-less it wasn’t until the middle of the 19th century, in England at least, that the more significant change happened, the move from unlimited liability to limited liability companies. The company limited by shares, both private and public, has gone on to become the predominant company form and remains so today.

With this change, a “share” was no longer an interest in the company’s assets and liabilities but only a claim on future profits. It became the company itself who owns its assets and liabilities. The concept of the legal person was established—it is the company, as a legal person, who sues or is sued. Many have pointed out that a more accurate term would be ‘no liability’, as a shareholder only stands to lose the value of their shares and has no liability for the actions of the company.

From a situation in which share owners were personally liable, and therefore had great interest in the actions of the company, the relationship between share ownership and an interest in control became less important, and thus the responsibility involved in ownership waned. That was the point at which this close relationship, where shareholders and directors were often the same person, started to become more separate.

Shareholder primacy

In a foundational governance text in 1932, The Modern Corporation and Private Property, Berle and Means raised a concern that the corporation might become ‘ownerless’, where directors become dominated by their managerial role rather than their supervisory one, and act in their own interests without accountability to their shareholders. Their logic was that if shareholders are the risk-takers they have most incentive for company success and are best placed to exercise control rights. This led to the idea of “shareholder primacy” where the primary responsibility of directors is the success of the company for the benefit of the shareholders, which would—they imagined—mitigate the decrease in director accountability to shareholders from the new form of corporations.

Shareholder primacy and the relationship between the company, directors, and shareholders still leads to confusion; for example, directors are the agents of the company; they are not agents of the shareholders. Shareholders have no right to instruct directors. They can elect, or not elect, directors, which might give the impression that they can instruct them, as it gives them indirect power and influence.

As an example of evolving to a more purposeful business, Paul Polman as CEO of Unilever has tried to turn this ownership convention on its head, urging shareholders to put their money somewhere else if they don’t buy into Unilever’s long-term sustainability value-creation strategy. He made it clear that short term speculative shareholders are not welcome, and shareholders should no longer expect to see quarterly reports along with earnings guidance for the stock market from the company.

This recognises that shareholders are not the only risk takers; there are others, including employees, suppliers, the environment, and wider society (particularly with examples like tax avoidance). This recognition exposes the flaw in shareholder primacy.

The shareholder ownership myth

The shareholder-centric view went on to become the dominant narrative and reinforced the idea of shareholders as owners. Despite shareholders no longer being the owners of company assets (or liabilities!) over 150 years later we still hear the assertion that they are.

They are not the owners of companies and there is no legal basis for this, they own shares with certain rights attached.

It is perhaps understandable why this myth persists as, at least partly, we still afford shareholders primacy and some ‘ownership’ rights. Here in the UK they include the right to vote on director elections as well as receiving a dividend, and in practice institutional investors try to exert their influence.

That the long-term interests of companies may conflict with short-term interests of many investors is obvious and is at the heart of the problem with the current model; we keep hearing calls to take a long-term perspective yet those leading companies believe they are there to satisfy masters with often short-term interests. There is an inherent conflict in the model which raises the question of how to evolve this otherwise almost inevitable outcome?

Is it time to reconsider the idea of shareholder primacy and the rights shareholders are afforded?

The maximising-shareholder-value myth

By the 1980’s another myth took shape: that there is a requirement for companies and therefore their directors to maximise shareholder value (MSV).

The implication is that the success of, and even the purpose of, the company is to MSV. There is no such requirement.

Unfortunately, the combination of soft-law standards of financial accounting and corporate governance codes “powerfully define the domains of accountability of corporate management in ways that support MSV” (see here). So MSV became locked-in in many ways:

- Executive pay being tied to stock price performance legitimised MSV which led to dividends and buy-backs where executives become beneficiaries

- Increasing short-term pressures on CEO’s (from shareholders) as demonstrated by the shortening of CEO tenure

- Encouraging cost-cutting, downsizing, and distributing cash to shareholders rather than investment in productive activities like research & development, capital investment, and employee development—and hence away from innovation. This is ultimately a race to the bottom.

- Encouraging mergers and acquisitions to show short-term returns, often at the expense of long-term value

- Encouraging financial engineering, and legitimising international tax (avoidance) structures, as being an MSV obligation

This combination of notions: shareholders as owners, shareholder primacy, and MSV, became the dominant ideology and persists to this day. As we have seen in recent years, it has caused enormous damage not the least of which are the privatisation of gains and socialisation of losses.

If MSV were a legal requirement, we might rightly question its wisdom. That it is not a legal requirement and yet is treated as if it were, belies rational explanation.

Thankfully this is now beginning to unwind (see examples here, here, and here).

The capital market myth

We are often led to believe that capital markets are the oil that lubricates the entrepreneurial machine, and that stock markets are central to this. This is greatly overplayed, as except for the initial investment, e.g., at the initial public offerings stage, purchasing shares does not provide capital to the company. It is simply the exchange of shares between buyers and sellers with no movement of capital to the company.

For the most part the stock market is not about investing capital in companies and more like a big betting outfit with winners and losers and money-making intermediaries. This has become more of an investment market where ownership and its responsibilities are less, if at all, relevant.

Where next

While obviously an issue for larger publicly-listed companies, all this is also relevant to smaller and medium-sized companies where it is easy to conflate the roles of shareholders and directors.

I find it interesting that despite the damming evidence for a failing model, there are plenty of companies doing a fantastic job, whether serving their customers and wider stakeholders (employees, communities, etc.) and rewarding investors, being purposeful businesses, or evolving to next-stage organisations. They are managing this under the current ownership and governance model, yet I sense the model is not actively supporting this evolution. While we see some examples of adapted company forms like B-Corp emerging, in the next article I will explore what practices would actively support next-stage organisations.

Dick Baker supports organisations to develop new ways of working to better reflect the complexity of the modern work environment. He specialises in organisational design, and governance systems and board practices across different sectors. He is a member of Future Considerations and is passionate about supporting the shift to a more purposeful organisational world. He can be contacted at dick@

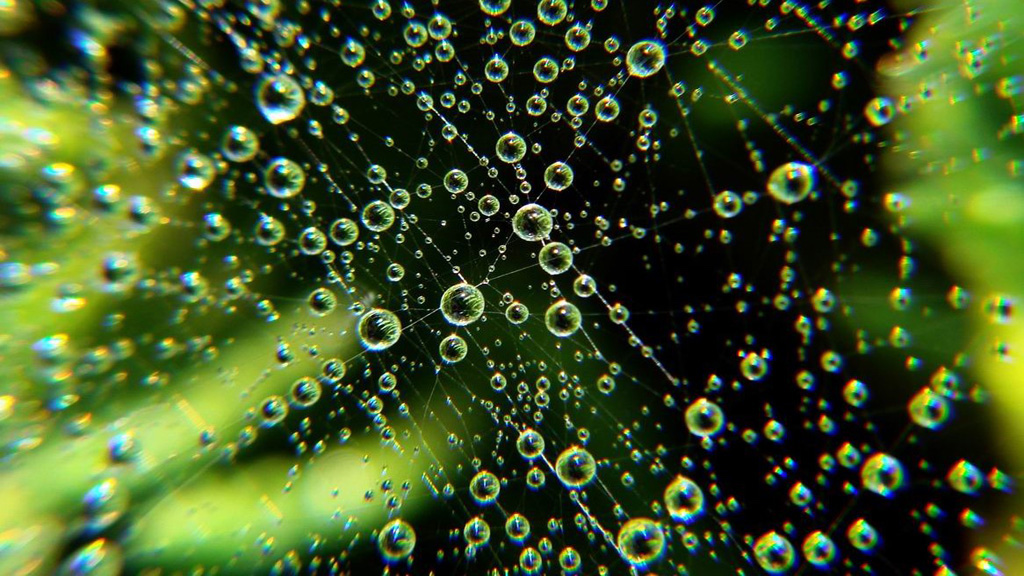

Photo credit for Featured Image/graphic link: Marek52 via Foter.com / CC BY-NC

hi Dick, thank you for taking up this subject. The ownership issue is really one of the important missing pieces in the Teal organisation jigsaw 🙂 Await your next article with anticipation 🙂

Without addressing the ownership issue any talk on “self-management” is very limited and limiting. A good exception is Encode.org, where all partners have equity! Enspiral is also interesting, but their model seems to be more a federation of cooperatives than a business that can perform large-scale coordination within the same enterprise.

I really really want to see humans develop more options for “ownership” in all arenas of life. I am aware of a couple of dozen, and there are more being invented all the time! What makes the matter even MORE complex than this article and Jon’s article show, is that ownership is a parsed concept, not a singular concept. Rights of use, sale/disposal, and modification are separable, so “owning” isn’t even a “something”!! Most conversations don’t even specify which of those rights is being referred to by the concept “own.”

I’d like to call attention to Oliver Sylvester-Bradley’s exploration of ownership in the form of worker co-ops; he briefly touches on that aspect in this EE Magazine article, and has written more elsewhere. https://enliveningedge.org/views/collaborative-organisations-internet-age/

And of course, there are various forms of “commons” emerging; George Por is very involved with some of those. One could go on and on!!

What I hope will emerge is some PRINCIPLES around ownership, based on fundamentals of economic life and going back even further to how the whole concept of ownership itself evolved, because for so many thousands of years for humanity, it was absent, and is still absent for many people in the world. What function does the concept of ownership serve in what kinds of human life and relating, and how is the concept used for well-being and how does it get to be used for harm?