By Charles Ehin for Enlivening Edge Magazine

As suggested by Peter Gray1 and other anthropologists our hunter-gatherer ancestors progressively practiced a system of “reverse dominance” that prevented anyone from assuming power over others. This was opposite to the alpha male and female patterns of some of our primate cousins.

Regrettably, the introduction of agriculture about 12,000 years ago and with it the accumulation of wealth by some and not others, gradually brought into play what I call “sanctioned dominance.” I propose, we are now finally in a “reverse dominance reclamation phase.” Human nature didn’t actually change when we began to settle down and till the soil, and now it is reasserting the “reverse dominance” pattern.

Sanctioned Dominance

What is “sanctioned dominance?” For me, one of the best examples is the traditional organizational chart still in use by most firms. It officially and clearly delineates the various levels of “sanctioned managerial domination” within a given organization.

Unfortunately, sanctioned dominance is a double-edged sword. It presents a sense of control and predictability but at the expense of thwarting the human predisposition to seek supportive relationships. However, supportive relationships form the basis for amplified organizational engagement and agility. Accordingly, annual Gallup Polls show “full worker engagement” in the US hovering around just 33 percent.

Specifically, dominance (attempted control of others) instantaneously generates subconscious resistance since it is a “perceived threat” to an individual’s self-identity and agency. Conversely, extended autonomy (self-management) instantaneously generates a feeling of personal control and acceptance since it’s a “perceived reward.” In strict top-down compliance-oriented organizations this positive response to autonomy might not “appear” to be true since people don’t respond to crumbs of autonomy, because they expect (and don’t want) to be reprimanded for stepping out of place.

We Space Theory

We Spaces—social spaces of supportive relationships—are not new. They have been “key features” of all social systems since the dawn of our species. They are key to not only our survival but also personal comfort. Thus, we are members of countless We Spaces throughout our lives. Yet, we pay little attention to them, especially in our formal/public institutions, since they tend to be “invisible,” conveniently tucked away in our subconscious minds.

We Space Theory focuses on the levels of supportive relationships—mutuality of cognition, experience and perception –within and between members of organizational units, leading to greater overall agility or the ability to effectively detect, assess, and respond to changing conditions. It’s best described by the old saying, “I have your back, you have mine.”

As suggested before, We Spaces are the “relatively small intimate and voluntarily formed well-being zones” that provide comfort and sustenance to all of us as much as possible. They are also key to the preservation of our individual identities. Within We Space everyone has “skin in the game” and is considered to be equal in status only differing in roles members assume. It’s the recognition by all that collaboration, instead of attempts at domination, are in the best interest of “everyone involved.”

Antonio Damasio2 and Tali Sharot3 make it quite clear that we innately rely on three key self-organization drivers for our actions and reactions:

- perceived threats or rewards

- causal agency/self-management

- emotion

For example, most people seek out folks who make their life enjoyable and rewarding while avoiding those who might lead to confrontations. We also relish autonomy, or being in control of our destiny, while avoiding being dominated by others. Finally, as Frans de Waal4 stipulates, emotions within an optimal range of intensity focus the mind and prepare the body for action while leaving room for experience and judgment.

Shared-Identity

In the constant inborn effort to maintain our individual identity, group size is a particularly critical factor in the necessary formation of high levels of supportive relationships. According to renowned British anthropologist Robin Dunbar5 we max out at about 150 people. Keeping a group to 30 or fewer people is the best option, probably because it roughly coincides with the average hunter-gatherer band size.

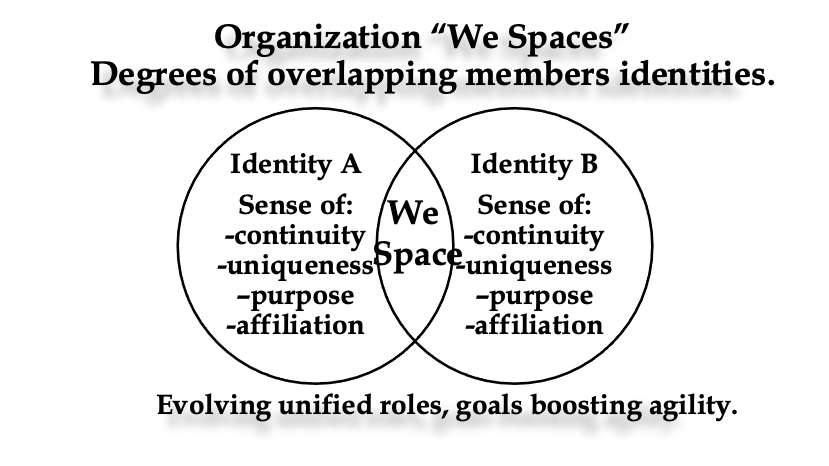

All of this brings into the play the most critical, but elusive, factor in We Space Theory; the evolving “shared-identity” as depicted by the figure below.6 Basically, a shared-identity “develops” over time mainly via self-organization and not by management edicts. This is not true only in theory but also quite observable in any experience of attempting to create it via decree. Yet again, we’re dealing with human nature and how we respond to perceived threats/rewards and restraints of individual causal-agency/autonomy all processed with emotions.

Conclusion

What we need to keep in mind is that We Spaces don’t develop overnight. From an organizational perspective We Spaces usually evolve in stages—compliance, cooperation, coordination, occasional collaboration and finally endless collaboration or We Space. As one can see, at each stage supportive relationships increase while transaction costs decrease progressively, while increasing productivity, innovation and organizational agility. Of course, the opposite is true in enterprises where sanctioned dominance is still alive and well.

“We Space” Theory brings to light our evolved predispositions for the practice of “reverse dominance” or self-management and the organizational pitfalls in restricting rather than promoting these fundamental tendencies. It’s all about harnessing the positive “inborn” dynamics (thinking, feeling and acting) that we all have in common yet also make us individually unique in the pursuit of common goals.

Charles (Kalev) Ehin is the author of three management books and numerous articles about engagement and self-management. He is also the originator of We Space Theory. Currently he is Professor and Dean Emeritus at The Gore School of Business at Westminster College in Salt Lake City, Utah USA. Contact him at [email protected]

Charles (Kalev) Ehin is the author of three management books and numerous articles about engagement and self-management. He is also the originator of We Space Theory. Currently he is Professor and Dean Emeritus at The Gore School of Business at Westminster College in Salt Lake City, Utah USA. Contact him at [email protected]

Key References

- Gray, P. (2019). “The Play Theory of Hunter-Gatherer Egalitarianism,” Psychology Today, August 31.

- Damasio, A. (2010). Self Comes to Mind: Constructing the Conscious Brain. Pantheon Books.

- Sharot, T. (2017). The Influential Mind. Henry Holt and Company.

- de Waal, F. (2019). Mama’s Last Hug. Norton & Company.

- Dunbar, R. (1996). Grooming, Gossip, and the Evolution of Language. Harvard University Press.

- Ehin, C. (2020). Expanding “We Spaces” Narrowing the Management Paradox. Book Baby.

Other Sources

Ehin, C. (2004). Hidden Assets: Harnessing the Power of Informal Networks. Springer.

Ehin, C. (2009). The Organizational Sweet Spot: Engaging the Innovative Dynamics of Your Social Networks. Springer.

Ehin, C. (2013). “Can People Really Be Managed?” International Journal for Commerce and Management, Vol. 23 (3).

Graziano, S. A (2019). Rethinking Consciousness. Norton. Harris, A. (2019). Conscious. Harper. Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking Fast and Slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Panksepp, J. and Bevin, L (2012). The Archaeology of Mind. Norton.

Reich, D. (2018). Who We Are and How We Got Here. Pantheon.

We need to talk about this and related subject much more seriously to save life on our planet. So, dear reader, please add to it as such as you feel is necessary in your own endeavors.

Delighted that Charles has taken the time to contribute this article and provide a brief overview of his We Space Theory (WST), something alluded to in the Enlivening Edge article here ..https://enliveningedge.org/tools-practices/does-doughnut-economics-need-star-enterprises/

Who now dare, I wonder, ignore “The Management Paradox” referred to in Ref 6 above?

Wonderful article Charlie! Understanding and correctly applying the principles of We Space Theory is critical for all organizations! Thank you for always diving deeper.

Professor Charles Ehin’s theory makes sense. Consider, for instance, the current Covid crisis in the country points, or the global climate crisis, for that matter. To a great extent, it is caused by a lack of shared identity and the perceived and/or real threats that sanctioned managerial domination has created to the human predisposition to seek supportive relationships.

Over many years, we have emphasized the individual in our social discourse and disregarded the guiding principle of our country: „we hold these truths to be self-evident that all men are created equal…..“.

For our country’s sustainability, it is time to advance the precepts of civic society and Professor Ehin’s book “We Space Theory” is a great contribution toward that end.

A great article. Encouraging a community of meaningful engagement ought to be a goal of any organization. The ideas presented here would seem to foster a better environment for a healthier workplace. Thank you for the article.

“Fascinating – and very closely linked to DeFi and blockchain development.” Gillian Tett author of Anthro-Vision and Chair Editorial Board, Editor-at-large, US at The Financial Times.

Great article, perspective and definition of “We Space.” Though this theory has been around very few academics have defined it as well nor business executives describe it. Understanding the theory which is at this point has enough scientific basis to be factual to improve systems. Optima Sports Group builds performance models for professional, amateur and fantasy sports. Those models translate extremely well into HR when We Space is applied to performance of a team and company.

The world would do well to listen to Charlie and focus on “we” vs. “I.” We would also benefit from listening to his sage wisdom around cognitive science and the brain’s “operating system” of which most of us are not aware and about which we learn very little. Without awareness, we will continue on a path of power over others (command and control) versus development of internal power (self-management) to our own detriment.

The concepts in this article seem to be not just interesting and useful for management today, but in particular are relevant for the post-Covid era, in which we are sorting out the particular details of how we work. While the author states that WeSpace isn’t necessarily a new idea, I believe it takes on various aspects of renewed thought as we develop different and sometimes new ideas of where, when, how and with whom we work, and in particular how we develop the WeSpace when at least 60% of Americans would prefer to work from home, and many will probably be allowed to do so. At best, this article raises many interesting points to ponder and further develop and apply!

Great article. I believe we truly are “hard-wired” for “reverse dominance” in smaller social groups of, as mentioned, around 30 individuals. Your article argues for this to be the goal in organizational settings where possible. I agree!