Written by Ash Buchanan and originally published on medium.com in Benefit Mindset

If you want to create a highly effective wellbeing program in today’s uncertain, volatile, and ambiguous world, you’re going to need a good map and compass. An inclusive and comprehensive set of systems tools to navigate the unique challenges you face.

In this article, we provide such a collection of systems tools. These tools are grouped into eight wellbeing wayfinding perspectives.

- Dimensions

- Wholeness

- Interconnectedness

- Awareness

- Complexity

- Development

- Transformation

- Leadership

These wayfinding perspectives have been curated for schools, communities and organisations who wish to take a systems approach to wellbeing.

Each perspective provides a unique and valuable lens through which we can make sense of, and respond to, our wellbeing challenges. The perspectives include a range of processes and organising frameworks that enable groups to engage in deeper levels of thinking, transcend limiting habits of thought and ask better questions to navigate the future in meaningful and highly adaptive ways.

A systems approach to cultivating wellbeing is suitable in cultures that are committed to collective learning and collective leadership. Effective implementation requires more than having the right tools. The quality of results created is dependent on making a collective commitment to a disciplined, developmental journey.

We hope you find these wayfinding perspectives useful in addressing your wellbeing leadership challenges.

Please note: This long form article is best read by downloading our PDF report. The wellbeing wayfinding perspectives are being shared as a ‘beta’ with an openness to discussing and developing them. If you have any reflections you’d like to share, we’d greatly appreciate hearing from you in the comments section.

#1. DIMENSIONS

“Health can be defined as a state of wellbeing, resulting from a dynamic balance that involves the physical and psychological aspects of the organism, as well as its interactions with its natural and social environment”- Fritjof Capra

Wellbeing is a multidimensional quality. Therefore, its valuable to have organising frameworks that comprehensively and inclusively bring together diverse concepts, domains of knowledge and wisdom traditions in useful ways.

Fritjof Capra’s Systems View of Life provides such a framework, identifying 4 organising dimensions;

Physical — Valuing the physical aspects of our wellbeing. This includes our behaviours, such as exercise, sleep and healthy nutrition. Our body traits; including appearance, strengths and weaknesses, immunities and disposition to disease and addiction. Useful references in this domain are broad and wide, spanning eastern traditions and western sciences.

Psychological — Valuing our inner lives of thoughts and feelings. This includes human qualities such as emotions, character strengths and shadows, states of conscious awareness, mindsets, motivations and spirituality. This dimension also includes a person’s ability to make meaning, construct identity, structure reasoning and form worldviews. Useful references in this domain include Positive Psychology, Martin Seligman’s Flourish and Ken Wilber’s Religion of Tomorrow.

Social — Valuing the way we come together, learn from and relate with others. Our wellbeing is interwoven with our culturally shared beliefs, values, higher purpose and the way we organise ourselves. Useful references in this domain include Robert Kegan and Lisa Lahey’s Deliberately Developmental Organisations and Margaret Wheatley and Deborah Frieze’s Walk Out Walk On. This dimension also includes the greater social systems we belong; including communities, cultures, health care, education, economic and political systems.

Ecological — Valuing our innate connection with nature and the environments we live. This includes daylight, air, water and food systems as well as the diverse community of life we share this planet with. Useful references in this domain include Edward O. Wilson Biophilia, Richard Louv’s The Nature Principle and Biophilic Design. This dimension also includes the design of the buildings and places we inhabit. Useful design references include the WELL Building Standard, Ester Sternberg’s Healing Spaces and Charles Montgomery’s Happy City.

The dimensions of wellbeing, based on Fritjof Capra’s systems view of life

Capra’s organising framework provides a comprehensive platform for facilitating cross-disciplinary dialogue about the diverse forces and patterns of relationships that influence wellbeing. Frameworks like this widen our circle of awareness so we can overcome fragmented thinking, oversimplifications and blind spots, and embrace a more complete account of the wellbeing challenge.

Other useful frameworks for exploring multidimensionality include Ken Wilber’s All Quadrants Integral Theory and multiple flows and capitalsframeworks.

#2. WHOLENESS

“Wholeness does not mean perfection: it means embracing brokenness as an integral part of life.” — Parker Palmer

Our second wayfinding perspective is rooted in the acknowledgement that all our lived experiences — both the positive and negative — the good and the bad — play a valuable role in our wellbeing. Wellbeing is more than the pursuit of happiness and pleasant experiences, it’s the wise embrace of opposites in our wholeness as a human being.

Learning how to accept, value and make conscious choices about our levels of wholeness is integral to becoming more fully ourselves. There is a gift and a challenge in every experience and the only way to actualise its life-giving potential, is by leaning into our experiences in a nurturing and well facilitated way. Therefore, rather than thinking in ‘either/or’ terms, or ‘this is better than that’ terms, wholeness challenges us to widen our embrace of opposites and think in ‘both/and’ terms.

Parker Palmer, author of A Hidden Wholeness, is one of the great writers about the value of living an undivided life. Finding union, authenticity and coherence between inner and outer life, between the desirable and the undesirable, is how we live lives that are congruent with the whole of who we are — both individually and collectively. Other useful references on wholeness include Paul Wong’s research and Frederic Laloux’s Reinventing Organizations.

When taking a wholeness perspective, a key aspect that stands out is the value of engaging in strength and shadow work.

Strength work — A concept from positive psychology is based on the idea each of us has a number of innate strengths of character that represent moral goodness and human excellence. For example, are you a creative person? A curious person? A humorous person? A kind person? When exercised, these strengths bring us more fully alive and elevate the contexts we belong.

Shadow work — It’s also wise to acknowledge that everyone experiences forms of trauma, dysfunction and inner conflict. We all have supressed parts of ourselves that we prefer didn’t exist. Over time, these darker aspects of our nature trigger us in ways we don’t want to be triggered, leading to destructive patterns and shadow crashes. Attending to our personal shadow — and our collective shadow — is vital to our wellbeing and ongoing development.

#3. INTERCONNECTEDNESS

“When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the Universe.” — John Muir

We are relational beings living in a profoundly interconnected world. Our wellbeing — including its physical, psychological, social and ecological dimensions — its strengths and shadows — are all interwoven through a vast web of inseparable and interdependent relationships.

The systems we belong to are also nested within larger systems. For example, individual students are nested within a school, and a school is nested within a larger school’s system. Each system is a coherent whole and also part of a larger system.

Therefore, our health and wellbeing is inseparable from the health and wellbeing of the systems we are nested and interconnected with. This includes the health of our social systems; including communities, cultures, societies, economic, political and education systems. It also includes the health of our ecological systems; our water ways, oceans, soil systems, food systems, forests, climate and the community of life we share this planet with.

In this context, wellbeing is best thought of as both a person centric quality and as an always adapting pattern of relationships. The result of participatory partnerships, something that happens in concert — within people, between people and in relationship with the broader community of life we belong. It’s a partnership that is increasingly in danger due to the unintended consequences of our collective actions — leading to today’s tragedy of the commons. Useful references on interconnectedness include Fritjof Capra’s Systems View of Life and Margaret Wheatley’s Who do we choose to be?

Bill Reed of Regenesis, is one of today’s leading writers about living systems and regenerative development. He suggests there are 5 progressive levels of partnership when participating with living systems;

Conventional — A partnership based on meeting minimum standards for social and environmental protection.

Doing less harm — A partnership based on arresting disorder and minimising negative footprints.

Sustainable — A life-sustaining partnership. Sustaining dynamic balance and healthy functioning.

Restorative — A life-enhancing partnership. Maximising positive handprints and doing good.

Regenerative — A co-evolutionary partnership. Catalysing mutually-beneficial transformations.

Five progressive levels of working with living systems.

“We all need one another — as individuals and as groups — to set up functional interconnections. Human beings, you see, need what a garden needs: a lot of diversity in functional relationships … all of the elements of life on earth are interconnected. Not only is no man an island, but no species is an island.” — Bill Mollison

Recognising the interconnectedness of systems is vital for seeing wellbeing as both an individual and a collective activity. Where the key question we ask ourselves is not only how we can flourish individually, but also, how we can collectively partner with the nested systems we belong. Creating communities of practice that support everyone with playing a unique and valuable role in our capacity to thrive. Creating the flow of multiple capitalsand dimensions of wellbeing that co-contribute to system health and resilience.

Other useful tools for working with interconnectedness include Design for Social Innovation, Transition Design, Social Labs, Appreciative Inquiry, Restorative Practices, PROSOCIAL, Ecoliteracy and Biomimicry.

“The amazing thing is, all the studies of longevity and happiness show that when you live a life realising your interconnected, you’re going to be happier and healthier.” — Dan Siegel

Psychiatrist Dan Siegel suggests that by honouring our interconnectedness, we recognise that helping others — is helping the self. Helping the planet — is helping the self. We thrive when the communities and ecosystems we belong to thrive. Also, when we feel connected to a broader humanity and a broader community of life, we gain an enhanced appreciation of our significance as an individual and how we can play a meaningful role in the world we live in.

#4. AWARENESS

“The quality of the results we create in any kind of social system is a function of the quality of awareness, attention, or consciousness the participants in the system operate from” — Otto Scharmer

Our capacity to take a perspective on the wellbeing challenge is integral to the quality of results we create. Therefore, its valuable to draw on processes that improve the quality of our awareness.

In this domain, Otto Scharmer’s U process is useful. The U process facilitates participants through three increasingly deeper states of consciousness to gain a more holistic appreciation of their challenges before responding. This includes;

Open mind — As the saying goes; the mind works like a parachute — it only functions when it’s open. Cultivating an open mind enables us to ‘see the world with fresh eyes’, ‘suspend judgements and habits of thought’ and ‘listen for information that challenges what we already know’. Associated with the virtue of curiosity, this gross-realm state of consciousness drives our desire to notice differences and seek new levels of understanding. It’s how we see beyond the threshold of the known and discover the unknown.

Open heart — Our capacity to redirect cynicism and listen with our hearts wide open. This includes our ‘ability to empathize’, ‘to see situations through another person’s eyes’ and ‘sense other perspectives’ from outside our current boundaries. This subtle-realm state of consciousness gives rise to our capacity to love together, suffer together and strengthen emotional connections — even when significant boundaries exist.

Open will — Our capacity to connect with the future that wants to emerge with a shared awareness of the whole. This includes the ‘letting go’ of our limiting beliefs and assumptions (e.g. ‘us vs. them’) and the ‘letting come’ of a new sense of self and of what is possible. How we can go beyond what ‘is’ — and become what ‘could be’. This causal-realm state of consciousness includes the courage to face our fears and cross the threshold of the known into the unknown with emergent creativity.

Otto Scharmer’s U process

These states of consciousness can be contrasted with what Scharmer calls ‘downloading’; reactively jumping from problems to solutions based on our old habits of thought and past judgements.

“The ability to shift from reacting against the past to leaning into and presencing an emerging future is probably the single most important leadership capacity today” — Otto Scharmer

The U process cultivates a social field for people — together with their organisations and communities — to get below the surface of their wellbeing challenges and tap into their collective capacities. These temporary shifts in conscious states shift’s the vantage point of our awareness, enabling groups to; illuminate their blind spots, become aware of unintended consequences and operate from a greater sense of the whole. In doing so, the U process puts collective wisdom, emergent potential and co-creative leadership at the centre of wellbeing wayfinding.

When whole systems operate from these increasingly deeper levels of awareness (e.g. a whole school or a whole education system), the system paradigm evolves. In turn, this evolution transforms the language used, levels of listening, levels of conversation, the way the system organises itself and coordinates with the larger systems its interconnected with. Refer to Scharmer’s book, Leading from the emerging future for examples.

Other useful frameworks for exploring awareness include Ken Wilber’s concept of waking up.

#5. COMPLEXITY

“Truly adept leaders will know not only how to identify the context they’re working in at any given time but also how to change their behaviour and their decisions to match that context.” — David Snowden & Mary Boone

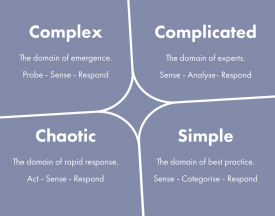

Given the systemic complexity of our wellbeing challenges, it’s useful to have wayfinding maps for guiding our actions in different contexts. In this domain, David Snowden’s Cynefin sense making framework is valuable. The framework describes five different contexts that are relevant to the wellbeing challenges we face;

Simple –The domain of good practice interventions. Contexts characterised by controllable, predictable, linear relationships that are obvious to everyone. The right answer is well known, self-evident and undisputed.

Complicated — The domain of expertise. Contexts characterised by controllable and predictable relationships that are knowable and repeatable. They are not obvious to everyone and require investigation and expertise to navigate.

Complex — The domain of emergence. Contexts characterised by unknown, unpredictable, uncontrollable, adaptive, interrelated and nonlinear relationships. The relationship between cause and effect is in constant flux and can only be known in retrospect. Patterns emerge from prototyping and safe to fail experiments so the path forward can reveal itself. These volatile and ambiguous contexts are best navigated with facilitation, coaching and presence based learning.

Chaotic — Contexts characterised by there being no knowable relationship between cause an effect. Leaders must first act to establish order, sense where stability and collective wisdom is present and respond by transforming the situation from chaos to complexity.

Disorder — Located in the centre, this condition applies when it is unclear which of the other four contexts is predominant.

David Snowden’s Cynefin sense making framework

The Cynefin framework highlights why approaches that work well in one context won’t necessarily work in another. Navigating wellbeing is not a one-size-fits-all proposition. As circumstances and contexts change, so must our approach and navigation styles.

“Complexity capabilities cannot be developed through more information. Instead, what is required is a deepening, diversifying, embodying, and personalizing of experience that enables complexity capabilities to emerge.” — Aftab Omer

This framework highlights why taking any off the shelf wellbeing framework or research finding and applying it to yourself, your people or your context is likely to have limited efficacy. Wellbeing frameworks and research findings are useful for navigating simple and complicated challenges. In complex and chaotic challenges, we need a navigation style based on discovering what makes a difference given the uniqueness of the people and contexts involved. In these conditions, the necessary knowledge to respond to our wellbeing challenges does not yet exist. A coherent way forward emerges from our collective wisdom in the act of attending to our challenges.

The Cynefin framework highlights why its valuable to think of wellbeing as both a learning and leadership challenge. A challenge that requires us to make sense of, and respond to, the ever-changing contexts we find ourselves. Adaptively navigating the known, the knowable, the unknown and the not knowable. Certainty and uncertainty. Our intended and unintended consequences. Our capacity to stay present, centred and grounded in fluid conditions where some things are guaranteed and others are not. Our willingness to experiment, fail early and often, and remain creative in our vulnerability.

#6. DEVELOPMENT

“When we experience the world as “too complex” we are not just experiencing the complexity of the world. We are experiencing a mismatch between the world’s complexity and our own at this moment.” — Robert Kegan

To meet the complexity of our wellbeing challenges, we also need to develop our own complexity.

From this perspective, Robert Kegan’s research on complexity of mind is valuable. As our mind matures and becomes more complex, we evolve through 5 stages of sense making maturity that transcend and include each other. Healthy unfolding of each stage is necessary to provide grounding for future stages. At each progressive stage of conscious development, our identity, worldview and the way we make sense of the wellbeing challenge evolves. Ideas, beliefs and values we have at one stage can seem less meaningful or simply inadequate at later stages of development.

Impulsive Mind — Identity and environment are fused. We have no sense of separateness. Wellbeing makes sense as meeting our basic needs to survive.

Instrumental Mind — Our emerging identity is defined by meeting our physical desires. Wellbeing is simply understood as the fulfilment of our desires.

Socialised Mind — Our identity is defined by the ideas and values of the culture, group or system we belong. Our self coheres by its alignment with, and loyalty to, that with which we identify. We are subject to our interpersonal relationships and mutuality and respond with individual needs, interests and desires. We make sense of wellbeing as having social and emotional health.

Self-Authoring Mind — We become aware of the social environment we belong and our identity is defined by our ability to self-direct, take stands and set limits for our lives within these systems. Our self coheres by its alignment with its own belief system, ideology, or personal code. We are subject to authorship and respond with interpersonal relationships and mutuality. Wellbeing is seen as a problem to be solved or as an adventure to be authored. It’s associated with achievement, engagement, self-esteem and the pursuit of positive or purposeful experiences.

Self-Transforming Mind — We become aware of the interrelationships between systems and respond with authorship, creative transcendence of identity and ideology. Our self coheres through its ability not to confuse internal consistency with wholeness or completeness, and through its alignment with the dialectic rather than either pole. We make sense of wellbeing as an adaptive, multidimensional and complex process. Wellbeing is seen as a process — as a process of becoming more whole and coherent with ourselves, others, nature and our everchanging contexts. It’s associated with contribution, purpose, being and wholeness.

Greater complexity of mind doesn’t guarantee greater performance, better interpersonal skills or improved wellbeing. It means we can hold greater complexity, ambiguity and paradox within our minds, which improves our capacity to make sense of, and take a perspective on, our wellbeing challenges.

“The real voyage of discovery consists not in seeking new landscapes, but in having new eyes.” — Marcel Proust

Kegan points out that until we have experienced a later stage of development, we are typically unaware of their existence. They are invisible to us, over our heads. Its only through the process of development — and becoming more fully ourselves — that our sense making matures and we see the world anew.

It’s also important to note that developmental stages don’t necessarily correlate with age. Different people unfold, plateau and recede in different ways. This means any group will likely comprise of a diverse range of developmental maturities who make sense of the wellbeing challenge differently. Therefore, it’s important wellbeing programs cater to a comprehensive range of meaning making capacities. This enables everyone to converge on the healthiest expression of their developmental stage, while also attending to their leading edge such that they can transform towards more complex capacities. Creating these conditions in an organisational setting is known as a Deliberately Developmental Organisation.

Other useful developmental references include Susan Cook-Grunters Ego Development Theory, William Torbert’s Action Logics and Jennifer Garvey Berger’s Changing on the job. In group contexts, Spiral Dynamics and Frederic Laloux’s Reinventing Organizations are useful.

#7. TRANSFORMATION

“You’ll never change things by fighting the existing reality. To change something, build a new model that makes the existing model obsolete” — Buckminster Fuller

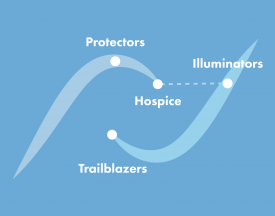

If we want to work with and transform the big systems we belong (e.g. education, business and health care), then it’s valuable to have maps for navigating how they change.

From this perspective, Deborah Frieze’s two loops map is valuable. Her research suggests that all dominant systems rise to their peak before turbulence starts to show and then move into decline. When this happens, the dominant system will try to innovate and remain resilient. But as Deborah suggests, you can’t fundamentally fix or transform big systems. You can only walk out of them and wisely walk onto emerging alternatives.

When systems start to decline and signs of turbulent show, new alternatives appear. Initially these new alternatives are created by a diverse group of trailblazers who have the courage to experiment with the future today. Over time these communities name the common change they are working towards, connect with each other, self-organise to nourish their collective efforts and illuminate their stories so others can find them. New transformative wellbeing paradigms are created, not by changing the existing system, but by creating communities of practise who courageously walk out of their limiting beliefs and language to take control of their own future.

This trailblazing work can be challenging, because as new alternatives emerge the powerful within the dominant systems tend to ignore or crush them in the interests of self-preservation. But if the alternatives band together in well organised communities of practise and exchange information, they can disrupt the declining system by co-creating a healthier new system.

To create healthy new systems, Debora highlights four roles we can play. This includes;

Trailblazers — People who are eager to be free and experiment with a healthier and more resilient future. Our pioneering path finders.

Hospice workers — People who compassionately stay within the collapsing systems and guide its people through the transition to the emerging alternatives.

Illuminators — People who tell the stories of the emerging system so others can find them and join them and to make wiser choices about their future.

Protectors — People who have the power in the dominant system to create space for innovation and experimentation with giving birth to the new.

Deborah Frieze’s two loops map

Without these roles, the systems we belong run the risk of declining without a healthier future to walk onto. Arguably this decline is happening to many big systems today — including education, healthcare, business. In turn, the declining systems are contributing to a broad range of health and resilience challenges for the people living and working within them.

Our health is inseparable from the health of our systems. Therefore, it’s valuable to have a range of these roles within our local communities and organisations to steward the reinventive and transformative potential of the systems we belong.

#8. LEADERSHIP

“The deep changes necessary to accelerate progress against society’s most intractable problems require a unique type of leader — the system leader, a person who catalyses collective leadership.” — Peter Senge, Hal Hamilton, & John Kania

Effective leadership of system based wellbeing efforts requires more than having the right tools. The results we create are highly dependent on who is leading. Therefore, the final wayfinding perspective is the role of leadership. From this perspective, Peter Senge, Hal Hamilton & John Kania’s concept of systems leadership is valuable.

A systems leader is a person who creates the conditions for, and brings forth collective cultures of learning and leadership. They are catalysers of our collective wisdom, our collective creativity and our collective potential in service of our common challenges. Systems leaders invite whole cultures to widen their circle of compassion, find unity in their diversity and create synergistic networks of collaboration to meaningfully respond to their wellbeing challenges.

Peter, Hal & John suggest system leaders require 3 key qualities. This includes;

- The ability to see the whole systemin relationship to other systems — a system of systems view.

- Fostering reflective and generative conversationsabout how our beliefs and assumptions manifest on a larger scale.

- Shifting the collective focus from reactive problem solving to co-creative future making.

Cultivating systems leader qualities is usually the result of a long, disciplined developmental journey. It typically requires many years of reflective work before we possess sufficient inner perspective to facilitate these complex collaborative efforts. Just because a leader knows about systems tools doesn’t mean they are able to facilitate and actualise their potential. Leaders are critical participant’s in sensing and actualizing what wants to be expressed through the use of systems tools.

Other useful references include Margaret Wheatley’s Who do we choose to be? which is particularly relevant for systems leaders navigating chaotic contexts.

Dancing with systems

“We can’t control systems or figure them out. But we can dance with them” — Donella Meadows

“You can’t stop the waves, but you can learn to surf” — Jon Kabat-Zinn

Why do these wayfinding perspectives matter? Very simply, because we can’t change what we don’t notice.

These wayfinding perspectives are tools for making the invisible visible. Tools for comprehensively seeing and inclusively navigating the systemic nature of our wellbeing challenges.

The strength of systemic based practices is in how they empower collective learning and collective leadership within our unique contexts. Empowering local schools, communities and organisations to see, and self-organise in response to, the patterns of relationships that bring themselves and their contexts more fully alive. Enabling us to author deeply meaningful and highly adaptive narratives that are coherent with who we are — and who we want to become. This is the essence of how we navigate the future in a healthy and resilient way.

Taking a systems approach to wellbeing is suitable in cultures that are committed to collective learning and collective leadership. Effective implementation requires the appropriate tools, systems leadership and a shared commitment to a disciplined developmental journey.

We believe taking a system-based approach is a significant and essential cultural leap society will need to make if we want to remain resilient in the 21st Century.

If you’d like support with taking a systemic approach within your school, community, or organisation, connect with us via Cohere, our wellbeing co-design partner.

If you have any reflections you’d like to share, we’d love to hear from you in the comments section below or you can comment at the original publication site.

Download original article as a PDF report

Republished with permission of the author.