By Gideon Rosenblatt and originally published on Alchemy of Change

We live in a society that’s become intractably resistant to the large-scale changes necessary for its own survival.

We live in a society that’s become intractably resistant to the large-scale changes necessary for its own survival.How do we overcome this resistance? Where are the levers? Theories abound on the left, right and in the center, many pivoting off different notions of “agency” and how influence actually moves through society. Are the levers of social change with the individual or the institution? If it’s with institutions, is it government, business, or the non-profit sector?

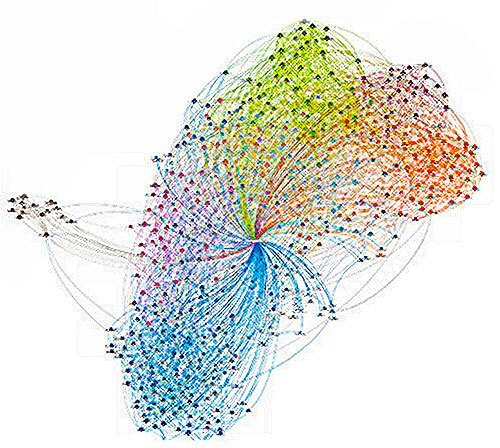

Network theory is a science of connection, and a useful frame for understanding the relationships that channel flows of influence in social change movements. To see a social movement with the eyes of network theory is to see the movement as a network.

Network theory is a science of connection, and a useful frame for understanding the relationships that channel flows of influence in social change movements. To see a social movement with the eyes of network theory is to see the movement as a network.

To apply network theory to social movements, we need to agree on the fundamental unit of connection; the ultimate entity that actually connects a social movement. Institutions matter, but putting individual human beings at the center of our analysis makes for a far richer, far more dynamic understanding of social movements.

In short, social movements are, first and foremost, networks of connections between people.

While we may speak of this organization connecting to that organization, this perception is an illusion. There may well be a day when software enables organizations to connect directly with one another without human intervention, but today

While we may speak of this organization connecting to that organization, this perception is an illusion. There may well be a day when software enables organizations to connect directly with one another without human intervention, but today

connections between organizations always happen through an underlying human connection.

People in this organization have relationships with people in that organization. When those relationships coordinate work between the two organizations, we sometimes simplify the situation by saying that the two organizations are “connected.” But the deeper reality is an underlying human connection.

This is not to discount the important role institutions play within social movements, and this is a crucial difference between the social movements of today and those that so rocked our society in the 1960s. Institutions are now a much bigger part of the overall social change landscape today.

After the large-scale social unrest of the 1960s and early 1970s, much of the energy behind social change efforts shifted to more formal institutions, many of which reside in the larger nonprofit sector, which includes some 1.6 million organizations in the United States alone.

After the large-scale social unrest of the 1960s and early 1970s, much of the energy behind social change efforts shifted to more formal institutions, many of which reside in the larger nonprofit sector, which includes some 1.6 million organizations in the United States alone.

This sector contributes over $750 billion a year to the United States’ economy (roughly 5.4% of the United States’ GDP) and has become an important source of jobs and economic stability to nearly nine million people.

Though social change organizations are just a subset of the larger nonprofit sector, they too, represent a move toward increased institutionalization. Institutions formalize relationships. They create structure, process and order to augment human connections. In this way, they helped transform the free-flowing social change movements of the 60s and 70s, crystalizing them into a social change sector.

A Bigger Sense of Organization

Placing the individual at the center of our perspective is important because it helps shift our understanding of what we mean by the word “organization” in the first place.

Placing the individual at the center of our perspective is important because it helps shift our understanding of what we mean by the word “organization” in the first place.

We can use the word ‘organization’ as a noun, and when we do, we’re usually talking about institutions. But we can also use the word ‘organization’ as a verb, and in this case, it takes on a broader meaning; something more akin to organizing, or “the coordination of human effort.”

Organization is bigger as a verb than it is as a noun.

In a social change context, “organization” can often mean a formal institution, but it always means the “coordination of human effort.” This networked perspective on organization is action-oriented, like a verb; it’s about the connection that occurs between people, regardless of whether or not they work in a formal institution.

How Today’s Movements Are Different

This focus on individual agency, on the individual’s ability to exert influence and power, isn’t just some philosophical stance or convenient approach to applying network theory to social movements.

This focus on individual agency, on the individual’s ability to exert influence and power, isn’t just some philosophical stance or convenient approach to applying network theory to social movements.

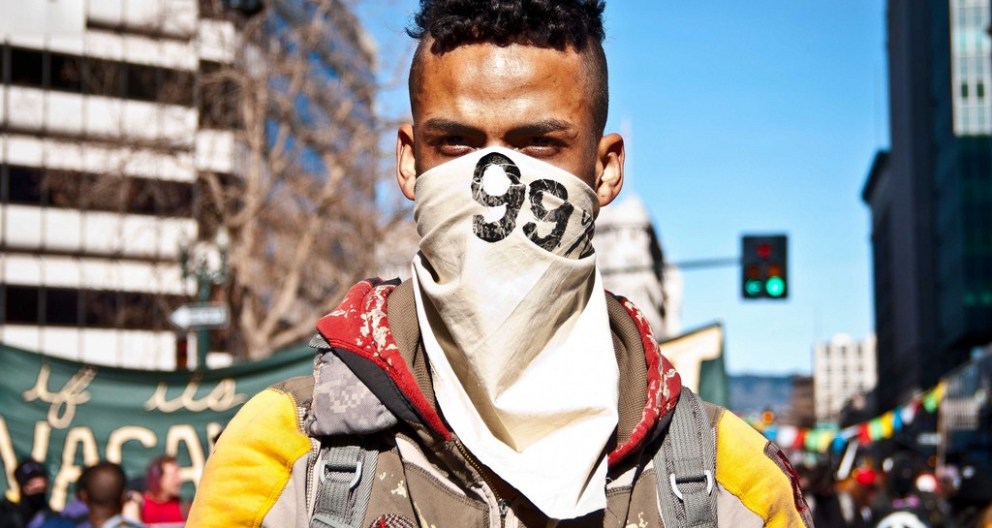

It represents a palpable shift in society; one fueled by the rise of online social networks, and communication technology more broadly. We see the rise in loose-knit coordinations of individuals in the 1999 World Trade Organization protests in Seattle, and more recently in the Arab Spring and the Occupy Movement.

The resurgence of loose-knit organizing represents a counterforce to the increased institutionalization of the professional social change sector; a breath of new life for social movements. And though the Occupy Movement and the Tea Party share many similarities with their precursors from the 1960s and early 1970s, they’re also different in important ways.

The first, and most obvious difference is the way technology plays a critical role in maintaining connections and enabling loosely coupled collaboration across large numbers of people. Mobile phones, YouTube, Twitter, and Facebook play critically important roles in helping these new, more networked movements to stay coordinated with minimal organizational overhead.

The first, and most obvious difference is the way technology plays a critical role in maintaining connections and enabling loosely coupled collaboration across large numbers of people. Mobile phones, YouTube, Twitter, and Facebook play critically important roles in helping these new, more networked movements to stay coordinated with minimal organizational overhead.

The second difference has to do with how these new networks deliberately adopt networked organizing techniques to run themselves. Tea Party activists regularly cite “The Starfish and the Spider: The Unstoppable Power of Leaderless Organizations” as a kind of Bible for understanding the decentralized, peer-to-peer organizational structure of their movement.

The second difference has to do with how these new networks deliberately adopt networked organizing techniques to run themselves. Tea Party activists regularly cite “The Starfish and the Spider: The Unstoppable Power of Leaderless Organizations” as a kind of Bible for understanding the decentralized, peer-to-peer organizational structure of their movement.

The Occupy Movement continues to refine and develop organizing processes that are the epitome of non-hierarchical, networked approaches to coordination. They are very deliberate in all of this, freely sharing their innovations as a kind of “open-source” set of processes that make them incredibly easy to spread from location to location.

The other big difference between modern social change networks and those that existed in the 60s is their existence within the context of a well-established social change sector; something that was still quite embryonic in the 1960‘s.

Today, when we speak of social change movements, it’s not completely clear what we mean. Are we talking about the social change sector, just those institutions formally dedicated to social change? Are we just talking about the more loosely structured networks like Occupy Wall Street? Or are we talking about some hybrid that includes both, and if so, how do these two very different approaches to social change connect with one another?

Over the next few months, I’ll be building on some work I did several years ago to try to better integrate these two very different approaches to social change; by re-imagining the movement as network.

Republished under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Featured image, block quoting, and some paragraph spacing added by Enlivening Edge Magazine.