By Henk Hadders for Enlivening Edge Magazine

As organizations are evolving towards Teal, accounting and reporting systems have to evolve as well. In this article I claim that our mainstream sustainability measurement & reporting systems are still unfit and dysfunctional, and I describe some functional specifications for better solutions in the future.

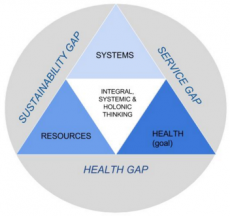

This is Part 3 of a 7-part series about the elements of a new social contract for health and sustainability. Part 1 and part 2 can be found here and here. In Part 3 I explore the relationship between systems and resources or the Sustainability Gap (see Diagram 1). Each system or organization has to ask the question: Are we sustainable and if not how big is the gap?

How efficient are our human (artificial) systems /organizations at using vital capital resources sustainably ? How to measure and report the sustainability of the impact of organizational activities on the stock of multi-capital resources ? How to measure and assess the sustainability of the impact performance of business organizations, healthcare organizations, etc. on the vital capital resources needed for our well-being and health ?

High Quality Sustainability Performance

Organizational performance measurement and management is focused on measurement and indicators for input, process, output, and outcome. It’s about efficiency and effectiveness in the results chain. Sustainability performance measurement and management is about a fifth category: impact; it’s about measuring what the impact is of a certain performance outcome on the stock of vital capital resources. Others use an “outcome-asset impact model” to highlight the relationship between outcome, vital capitals and impact. The International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC) gives a good illustration of this value creation process using a spider diagram in their Framework (see page 13).

As an Executive Director of the Board in mental health, I was very unhappy with the theory and practice of mainstream sustainability management, measurement, and reporting. Most sustainability reports in healthcare don’t say a thing about true sustainability performance of organizational primary and secondary processes and activities. It’s about outcomes rather than about impacts. They don’t take impact on multi-capitals into account. What is also badly missing are standards of performance and “sustainability context”, making nearly all these reports completely context-free.

The main de-facto standard in the world for sustainability measurement and reporting is the guidelines of the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI). Although GRI adheres to the importance of “Sustainability Context” in its principles, it badly fails to operationalize this in its guidelines for organizational use. All of this has made me an advocate of a new approach: “Context-Based Sustainability” (CBS).

We need to evolve towards new context-based sustainability measurement and reporting systems for healthcare organizations. (We also need to re-imagine a new Multi-Capital Health Impact Assessment (HIA) Scorecard incorporating a set of footprints each associated with a specific determinant of health and its vital capitals resources). In this article I will describe the functional specifications of such a needed approach, but first I introduce the importance of context.

Context – an introduction

In 1992, the importance of context appeared in the sustainability debate during the Rio summit, and was formulated in Agenda 21. Whereas many instruments are offered to measure sustainability (e.g., reporting guidelines of GRI, the integrated reporting framework of IIRC, the work of Sustainability Accounting Standards Board, or the Global Initiative for Sustainability Ratings), so far they do not incorporate context in their measurements.

In 1992, the importance of context appeared in the sustainability debate during the Rio summit, and was formulated in Agenda 21. Whereas many instruments are offered to measure sustainability (e.g., reporting guidelines of GRI, the integrated reporting framework of IIRC, the work of Sustainability Accounting Standards Board, or the Global Initiative for Sustainability Ratings), so far they do not incorporate context in their measurements.

The necessity of including context in sustainability in general, and sustainability measurement more specifically, comes from the notion that sustainability does not operate in the same way at different places, and different times. The variation of capabilities and capacities over the world is too wide to take one specific sustainable norm for e.g., air and water pollution, use of renewable resources, etc.

This article sets out to draw the contours of context-based sustainability measurement, providing a functional specification for doing so. The functional specification will be too abstract for immediate application. Yet, it sets the playing field within which indicators operating at the grassroots level will be formed. The initial focus of the functional specification is on the organizational context. Hence, it specifies (1) the criteria the measurements of an organization should meet and (2) the procedure that needs to be followed in order to meet these criteria.

“Sustainability requires contextualization within thresholds. That’s what sustainability is all about” ~Allan White Co-founder, Global Reporting Initiative, Founder Global Initiative for Sustainability Ratings

The main idea is that the measurement and reporting of organizational sustainability needs to be done relative to norms, standards, or thresholds. These norms, standards, and thresholds relate to the impacts of the focal organization on human, social, natural, and constructed capitals. Measured indicators are evaluated against the norms, standards, and thresholds, to determine if activities are indeed sustainable (i.e., are they meeting the norm, standard, or threshold level(s)). The norms, standards, and thresholds are set such that these guarantee that the capitals they relate to will not be degraded by their use, and preferably will be enhanced or strengthened. In the following section I provide the main concepts and a functional specification for context-based measuring and reporting.

Functional specification

Relationships: Sustainability context ultimately derives from the relationships organizations have with their stakeholders and other parties whose interests and well-being are affected by an organization’s actions, or whose interests and well-being ought to be affected, given the relationships involved. Any procedure for incorporating sustainability context in measurement and reporting should therefore integrate stakeholder perspectives as a major component of context;

Impacts on capital stocks: Procedures for incorporating sustainability context in measurement and reporting should deal explicitly with both actual and normative organizational impacts on capital resources of vital importance to stakeholder well-being, namely stocks of natural, human, social, and constructed (or built) capital;

Allocations and performance standards: Such procedures should result in specific allocations of either (i) the carrying capacities of natural capital stocks, or (ii) the shared or exclusive burden to produce and/or maintain anthropogenic capitals (i.e., human, social, and constructed capital stocks) to individual organizations. Such allocations should serve as the basis of setting performance standards for determining whether or not an organization’s actual impacts on vital capital stocks are sustainable;

Generalizable: Such allocations should be reflective of duties and obligations owed to stakeholders to use and/or produce vital capital stocks at levels that are fair and proportionate and which (i) would help to ensure stakeholder well-being if applied to all members of contextually relevant, responsible populations, and (ii) would not exceed available stocks of natural capital or fail to produce and/or maintain stocks of human, social, or constructed capital at levels required to ensure stakeholder well-being—in short, the allocations should meet the “what if everyone did the same thing?” test;

Context-Based Metrics (CBM’s): The procedure should involve the use of context-based metrics of some kind that express performance in terms of impacts on vital capitals relative to organization-specific standards of performance (or thresholds) for what such impacts must be in order to be sustainable.

In general, it is strongly advised that any report that aims to describe the sustainability performance of an organization should disclose impacts on vital capital stocks relative to norms, standards, or thresholds for what such impacts would have to be in order to be sustainable. Any procedure that conforms to the functional specifications set forth above will comply with this requirement. Reporting organizations should feel free to employ a procedure of their own that allows them to do this.

A possible procedure

To put the functional specification explained in the previous section to use, a five-step procedure is provided to illustrate a possible implementation of the specification. The five steps of this procedure are (1) identification of stakeholders, (2) identification of relevant impacts on vital capital stocks, (3) determination of normative impacts on vital capital stocks, (4) determination of the actual impacts on the vital capital stocks, and finally (5) determination of the sustainability performance. These five steps are briefly explained below using an example of water usage as CBM, or “water footprint.”

Regarding the use of water in an area, stakeholders are those people who rely on and/or make use of the same water resources the focal organization uses in the same watershed. These may be the citizens of the village or city nearby the organization’s factory, but also the next-door agricultural business should be considered a stakeholder. Key is the question of who is in any way affected by the organization’s use of the water resources.

Regarding the use of water in an area, stakeholders are those people who rely on and/or make use of the same water resources the focal organization uses in the same watershed. These may be the citizens of the village or city nearby the organization’s factory, but also the next-door agricultural business should be considered a stakeholder. Key is the question of who is in any way affected by the organization’s use of the water resources.

In the second step, the identification of relevant impacts on vital capital stocks is done, which in this case are the used water resources. Setting the norm of how much water the organization is allowed to use, is determined during the third step. The allocation of a ‘fair share’ to the organization should be based on some relevant criterion.

Once the norm is set, the actual impact of the organization on the water resources needs to be determined. How much water is actually consumed? Finally, the actual impact (A) is plotted against the set norm (N). In case an organization is allocated a norm of say 100,000 litres water consumption per year and the actual consumption has been 110,000 litres, the conclusion is that the organization is not sustainable; the organization has consumed more than its fair share.

Sustainability performance (S) = A/N, [sustainability equals actual impact divided by the set norm] where for ecological areas scores less than or equal to 1.0 are sustainable and where for social areas the scoring conventions reverse and scores of more than or equal to 1.0 are sustainable.

Discussion

Departing from my experience in healthcare, this article has provided some functional specifications of the way context-based sustainability measurement and reporting can be shaped. As indicated earlier, these functional specifications are too broad to allow for immediate implementation. Yet, they provide some footholds to already start thinking how such implementation may be realized. Existing initiatives (e.g., GRI and IISD) provide extensive sets of indicators measuring various aspects of sustainability.

However, without some norm, I argue that actual sustainability performance on these indicators cannot be determined in a meaningful way (both in healthcare as in business).

Some readers might ask: Can this really be done? The answer is: Yes, it can be done. Individual metrics have been proven in practice in several organizations within the past years.

Why don’t you join us for their further development and application ?

In case you want to know more about CBM’s, check out some of the open-source templates at the Center for Sustainable Organizations, such as a context-based carbon metric and context-based waste metric,

From the healthcare sector we keep targeting the Global Reporting Initiative’s fourth generation of sustainability reporting guidelines, pleading to adopt the principle of context-based sustainability measurement. Until then healthcare organizations using GRI guidelines will not produce true sustainability reports.

But I’m afraid the development and evolution of sustainability measurement and reporting systems will not come from the big mainstream institutions but from pioneers and organizations “with the passion of the explorer” such as : Mark McElroy and his Center for Sustainable Organizations, Ralph Thurm and his Reporting 3.0 Initiative, and the ThriveAbility Foundation from Bill Baue, ….and others. They truly are on a Hero’s Journey !

Acknowledgement

I thank Niels Faber (Radboud University, Nijmegen) for his advice and support

Henk Hadders is a former Executive Director of the Board of a Mental Health Institute in the northern part of The Netherlands. After his retirement, he started PhD research about sustainable health, sustainable healthcare. and sustainable innovation. Email [email protected]