By Rudy P. Friesen for Enlivening Edge

Although this article is primarily looking at long-term care, I want to consider all levels of care and am keen to explore with you how the three Teal breakthroughs can inspire the creation of next-stage long-term care facilities which are life-giving to both givers and receivers of care and which provide care that is affordable and nurturing instead of life-limiting, drug-managed, and ghetto-izing.

We are all getting older. How many of us want to spend our last years warehoused in sterile long-term care institutions? Not me. How could the three Teal breakthroughs that Laloux describes in next-stage organizations—self-managed teams, wholeness, and evolutionary purpose—inspire long-term care?

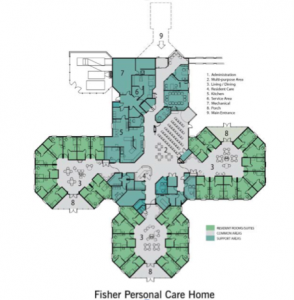

Essence of household LTC

The household model of long-term care (LTC), with its humanistic drive to create homelike environments for residents, is the leading edge of LTC today. As an architect, I have advocated passionately for this model for nearly two decades. Compared to the traditional, medical/institutional model, I feel it is currently the best option.

Generally, the household model:

- is resident-centred; an individual resident’s needs come first. In some cases, residents are encouraged to become partners in developing their own care plans.

- offers a home-like environment that is familiar to its residents, creates a household with an open kitchen at its heart, with family-style dining, and gives access to the outdoors.

- allows for flexible schedules; residents rise, eat, and bathe, when they wish, and follow familiar routines;

- employs self-managed caregiver teams that are committed to each household; they prepare meals, do housekeeping, arrange activities, and spend time with residents.

As a result, residents eat better, they need fewer drugs to manage their health or behaviours, their health is better overall, and they are less lonely because caregivers spend more quality time with them. Overall, the quality of care is higher, and this translates into happier stakeholders (residents, families, and staff). Operating costs are on par with, or lower than, traditional nursing home facilities.

But there are limitations. This approach to LTC is still paternalistic. Residents are basically incarcerated and ghetto-ized. Staffing structures are hierarchical and still too costly. Residents are not treated as whole people. Caregivers are not encouraged to bring their whole selves to work. While these organizations have mission statements, I have not seen evidence of an evolutionary purpose.

Strangely, cartoonish copies of the household model have emerged: themed villages; caregivers as costumed gardeners, hairdressers, shop clerks, and clowns; and a make-believe world based on a misinterpretation of Reminiscence Therapy. Residents are treated as children in arrested development.

Exemplary expressions of the model

Still in its infancy, the household model is poking its way slowly into various parts of the world.

The Green House Project is a franchise that provides services to profit and non-profit developer organizations. With close to 200 homes in various facilities, this model has contributed the most to changing long-term care in the US. Even so, this is a drop in the bucket since there are 15,700 nursing homes in the US, which house 1.4 million residents.

Initially they were envisioned as individual free-standing buildings located in groups or within existing residential communities. They are evolving into multiple households within multi-storey structures. And more recently, into two-household buildings integrated into communities.

Studies of the Green House model show that quality of care is very good. Financial performance is on par with conventional nursing homes, and there is very little difference in operating costs. When I visited a Green House facility recently, I sensed that, while the character of the home was residential, the scale of it still bordered on the institutional.

HammondCare is a pioneering, non-profit organization in Australia that provides various healthcare-related services including serving people with dementia. It has around 56 households of varying sizes. The preferred number of residents is between 8 and 12, depending on the level of care required.

Each household looks and functions like a home with décor that is culturally and socially relevant, based on an understanding of the resident’s likely profile. In addition to meeting the physical and emotional needs of residents, this faith-based organization also nurtures their spiritual well-being.

The organization’s data indicates that, while overall operating costs for their household facilities are lower compared to their traditional facilities, capital costs are higher.

De Hogeweyk has garnered international attention for its village-like facility in the Netherlands. It serves elders with severe and extreme dementia. Each household/home has 6 to 7 residents. The residents help run their own households together with a care team that is dedicated to that household.

Residents are ensconced in their former lifestyles and in an aura of Dutch life.[1] De Hogeweyk presents as a microcosm of a Dutch city with streets, lanes, plazas, fountains, and shops.

When I visited the facility a few years ago, I was struck by the painstaking attention to detail. I was delighted to be invited into one of the homes and felt very welcome. There, couples were playing games together around the dining room table.

Residents are free to come and go as they please within the complex. However, all 23 homes or households are accessible only from outdoors. And there is only one controlled entrance/exit to the complex. I am heartened to hear that one of its founders aspires to integrate residents into the community as the next step.

This facility receives the same level of public funding from the Dutch social security system as traditional facilities. However, the capital costs of this village-like facility are higher, necessitating private donations.

Rudimentary to autonomous self-managed teams?

Since all three of the LTC household examples above employ rudimentary self-managed teams, they might be good candidates for autonomous self-managed teams. However, this requires a major philosophical shift among owners, franchisees, operators, and senior management. It also means changing the current bureaucratic organizational structure.

Buurtzorg offers glimpses into how self-managed teams in LTC facilities could provide better service at significantly less cost.[2] This non-profit homecare organization in the Netherlands employs more than 9,000 nurses who work in self-managed teams of 10 to 12.[3] Teams have a high degree of autonomy and are totally trusted.

A head office of about 35 people provides all administrative support. Because there is minimal bureaucracy, overhead costs are low. The whole healthcare system benefits: emergency hospital admissions are reduced, hospital stays are shorter, and clients heal faster.

Abbreviated to amplified wholeness?

There is no evidence that household LTC facilities encourage wholeness among staff or residents. For residents, wholeness is addressed via the visible, outer dimensions of home and lifestyle. In order to nurture true wholeness, owners, operators, and managers of these facilities need to accept that wholeness involves both individual and community aspects of life, and both inner and outer dimensions of its residents and staff.

Empowering people with dementia

Buurtzorg takes a multi-pronged approach to wholeness. A client is treated as a whole person: physical, emotional, relational, and spiritual.

A nurse’s whole life, personal and professional, is taken into account. Since there are no job titles, descriptions, or status markers, nurses naturally expand their sense of self and identity, and shape their roles.[4] The whole system is nourished when the needs of Buurtzorg and its clients dovetail with a nurse’s calling and joy. As well, the team’s collective intelligence, as a whole, informs decision-making.[5]

Mission statement to evolutionary purpose?

It is difficult to find evidence of an evolutionary purpose in household models of LTC. They do not seem to have a life or sense of direction of their own. Instead, they rely on mission statements, planning, and budgets. There is a widely-held fiction that people control an organization’s development. To move from trusting human intervention to trusting an organization as a living entity requires a massive shift in consciousness.

Buurtzorg, by way of contrast, allows the organization to evolve in a responsive and fluid manner.[6] It is committed to helping sick and elderly clients live more autonomous, meaningful, and healthier lives. And decision-making involves listening into that purpose, and sensing it through large group processes.[7] Change management is irrelevant because the organization is constantly adapting from within.[8]

Founder Jos de Blok is so committed to manifesting his organization’s evolutionary purpose on a larger scale that he explains his methods to competitors, advises them free of charge, and invites them to imitate his methods.[9] Profit is considered a lagging indicator, a by-product of doing what is right. And Buurtzorg’s growth has been phenomenal. [10]

Evolution is preferred by Dr. Margaret Hannah. She re-envisions healthcare as a living human system. Hannah examines the Nuka System of Care, an integrated, non-profit, healthcare system created by Southcentral Foundation that is owned by Indigenous people in Alaska. Nuka has achieved remarkable results and is recognized as a world leader in healthcare design.[11]

I wonder if LTC has enough time to evolve before the silver tsunami of aging boomers hits, and before the system hits the economic wall.

Revolution is advocated by Dr. Bill Thomas. Even though his Green House model has impacted LTC more than any other household model, he is frustrated by its relatively slow growth. Consequently, he is organizing Disruption Tours across the US to stir up opposition to conventional LTC. He is even pushing State governments to close the worst-performing care homes yearly.

I wonder if this approach will create pushback and ultimately slow change.

Emulation is encouraged by Jos de Blok. Fortunately, Buurtzorg is transparent. It operates according to principles that invite emulation, and its practices are well-documented. I wonder who is bright and intrepid enough to take a page from Buurtzorg, then speed up the development of household LTC, and take it next-stage.

Life conditions might affect if, how, and when LTC changes. It depends on how badly a particular LTC system is broken. If beyond repair, revolution may occur. And if conditions are supportive, evolution may happen. It also depends on the cultural, political, economic, and historical currents at play. American LTC organizations may be more amenable to revolution. European ones may gravitate toward evolution. Or we could be totally surprised.

What might inspire emulation? I believe that Buurtzorg’s principles and practices can be applied creatively to LTC. Thanks to its dramatic growth, Buurtzorg might offer a blueprint and serve as a beacon.

Pragmatics anyone?

Next-stage organizations like Buurtzorg could get into the LTC business, and provide the highest quality of care at the lowest cost. All levels of care would need to be taken into account.

The whole healthcare system could evolve, taking LTC with it. This requires significant regional and local nuancing. More importantly, it requires hefty political will, especially in jurisdictions which control healthcare fully.

Organizations which currently embrace the household model could modify their existing organizational structures. This may appeal to LTC leaders who are fed up with the current state of affairs and are hungry for something entirely new. Here, local regulations will come into play, as well as vested interests.

New and existing LTC organizations could embrace the next-stage organization movement. This might be attractive to entrepreneurs who are inspired by their principles and practices, and also to forward-thinking millennials who are itching to fix a broken system.

One way or another, LTC is bound to change. What if we put our heads and hearts together to sense what it wants to become, and how we can serve its development?

G. Allen Power, MD, author of Dementia Beyond Drugs and Dementia Beyond Disease says, “People who wonder whether the glass is half empty or half full miss the point. The glass is refillable.” People with dementia still have the capacity to develop and contribute.

If you believe the glass is refillable and that the three Teal breakthroughs that Laloux describes in next-stage organizations—self-managed teams, wholeness, and evolutionary purpose—can be applied to long-term care, I encourage you to get in touch with me at [email protected]. Let’s get real with creating long-term care facilities which are life-giving, affordable, and nurturing instead of life limiting, drug-managed, and ghetto-izing.

To find out what a Positive Living Environment looks like, check out the PowerPoint presentation HERE titled ‘Creating a Positive Living Environment for People with Dementia’.

References:

[1] Homes are available in 7 different lifestyles: urban, homemaker, artistic, Indonesian, well-to-do, traditional, and Christian. In some respects, these homes look much the same. However, the interior design of each home reflects its lifestyle, creating an ambience that the residents will recognize.

[2] In his game-changing book Reinventing Organizations, Laloux describes Buurtzorg in detail.

[3] Each team serves about 50 healthcare clients in a defined geographic area. There is no leader or boss. Teams are responsible for all tasks. They provide care, decide how many and which clients to serve, look after intake, planning, scheduling and administration, arrange office rental and décor, determine how best to integrate with the local community, select doctors and pharmacies, decide how to work best with local hospitals, and choose when to meet, how to distribute tasks, what training is needed, and whether to expand or split their team. They also monitor their own performance and decide on corrective actions.

[4] Head office is in a nondescript house in a small village, and nurses decorate their small community offices to make them their own.

[5] No individual can derail, impose personal preference, or dominate proceedings.

[6] Responding to outside prompting, Buurtzorg took a broader perspective of neighbourhood care: not just to inject medication or change bandages, but to help people have rich, meaningful, and autonomous lives. One team developed a new concept, a boarding house for patients, to give primary (family) caregivers a break, for a day or two. Another team member inherited a small farmhouse in the country, and transformed it into an example of a respite facility. The idea of boarding houses will run its own course. If it is meant to be, if it has enough life force, it will attract nurses to make it happen and carry Buurtzorg into a new dimension of care. In response to outside prompting, Buurtzorg has set up “Buurtdienst” (neighbourhood services) to help people with dementia handle domestic chores, using the same structure of small teams. It has also set up “Buurtzorg Jong” for young involved with social services. It is now exploring “Buurtzorg T” to provide therapeutic care in peoples’ homes in early stages of mental illness, and is looking at small-scale community living units for older people, as alternative to large, impersonal retirement homes. Also a possible different model of hospital is being looked at: small, networked units spread throughout neighbourhoods. In all cases, Buurtzorg responds to outside stimuli and tries to sense what is meant to be.

[7] New team members are trained to listen to the organization’s evolutionary purpose. Its importance is emphasized by the founder Jos de Blok’s attendance at all of these sessions. Large group processes involve meditations, guided visualizations, etc.

[8] Instead of searching for perfect answers, workable solutions and fast iterations are sought.

[9] The traditional concept of competition is irrelevant. For de Blok, it is not about market share or his personal success. Growth is not an objective in itself, only as it manifests the organization’s purpose on a larger scale.

[10] It has grown despite its emphasis on making its services no longer needed. This is not surprising since the Teal or next-stage approach unleashes tremendous energies when a deep hunger in the world meets a noble purpose.

[11] In Humanising Healthcare, Dr. Margaret Hannah states, “Between 1997 and 2007, the results have been remarkable: a reduction of more than 40% in A & E usage, a 50% drop in referrals to specialists, and a decrease in primary care visits by 20%.” SCF sources have also confirmed a 93% employee satisfaction rate in 2015.

Images:

– 1st image: ft3 Architecture Landscape Interior Design

– 2nd image: author

– 3rd image: UK Alzheimer’s Society

– 4th image: Southcentral Foundation

– 5th image: http://www.123rf.com/, Copyright: Paul Vasarhelyi

Rudy P. Friesen is passionate about changing the warehousing-and-drugging culture of long-term care. As a practicing architect for more than 40 years, he spearheaded groundbreaking, cost-effective, and practical solutions for elder housing. He now researches best practices around the world, influences policy and public opinion, and serves as an elder care consultant.

Response from Dr. Allen Power posted on his behalf.

Dr.Allen Power MD is the inspiring author of “Dementia Beyond Drugs” and “Dementia Beyond Disease”.

Hey Rudy,

Thanks for writing and for sharing your article. (I’ll be in Hungary myself in a couple of weeks, at Alzheimer’s Disease International.)

It was nice to read your thoughts. I appreciated your insights that looked past the superficial aspects of the various models and continued to challenge whether they truly change paradigms and enable evolution over time. I think that is an ongoing problem in that most people think in formulaic terms and don’t take the concepts as far as they need to go. I also agree that regulatory and reimbursement factors can be very limiting as well, even in small house models.

I feel the Green House homes that I helped open at St. John’s in Rochester go a lot further than most in that

(1) we moved them off our campus and integrated them into a multigenerational neighborhood, where there is a lot of community engagement (from shopping for groceries, to attending church, the YMCA, or holding a barbecue for the neighbors)

(2) they are not dementia-segregated, and

(3) St. John’s began with a strong Eden Alternative foundation, so that they have gone deeper into transformation of daily life than most Green House homes, and are committed to more of an evolutionary path over time.

I am intrigued by the Buutzorg concept and will need to read up on this further.

Thanks again for sharing and all the best,

Al

A big thanks to Al for his thoughtful and insightful response to the article. I agree with you, Al, that your Green House homes in Rochester are great examples of connecting residents with the community. In fact I had them in mind when I referred in the article to “two-household buildings integrated into communities.” Thanks for elaborating on

their unique strengths. I plan to tour them at my earliest convenience.

You’ve also made me aware of the Austrian village of Strem, an example of a multigenerational community that weaves the lives of its elders into every aspect of the community. I plan to visit Strem on my way to the IEC conference.

And, yes, Buurtzorg is intriguing. It’s success as a “next-stage” organization is truly inspiring.

Rudy

On August 30 2015, a Sunday, I happened to listen to Companies without Managers BBC R4.

This programme was to change my life. For the first time I heard accounts of organisations treating people as individuals and as valuable human beings with all their idiosyncrasies. More surprising perhaps was that these companies were not only successful but they were astonishingly successful. I had to find out more, were these just oddities?

As I researched this phenomenon, I found examples of new ways of looking at seemingly disparate but inextricably connected concepts – from macro -economics, to work, health and welfare with much in between. Evidence of huge shifts in the way people are engaging with all facets of our world.

It also seems we do have a chance to change the world for the better; a very real chance and some are already on that journey.

The changes required are vast and complex, so where does one begin? I consider that the new models of working – self-organising, self-managing, less managers, Teal, sociocracy and so on (the concepts that first drew me in) are the key. As more organisations embrace these models and attitudes, other changes are likely to follow.

That said, I also believe that we MUST educate ourselves on the bigger picture, as much to have a clear idea of the urgency as to get a sense of direction.

So, whilst there is clearly a need to encourage/educate/help/mentor most organisations to adapt to the truths of what makes us human, the healthcare sector is (to me) the most in need. It is where we should concentrate. As whilst the ways many organisations operate are disappointing and some are disturbing, healthcare can be truly shocking, and possibly none more so than end-of-life care.

For change practitioners, healthcare does however have several big pluses. The basis for care is, or should be, compassion – which is one of the hardest lessons to teach in a standard organisation. Healthcare is also clearly about people – whereas other industries can fool themselves into thinking they are about nuts and bolts/marketing or whatever.

If we can get healthcare as an exemplar, then other industries might follow and if other industries follow, then maybe the related elements in the bigger picture will start on a healthier path.

Coda

The most startling part of the above article is that here we have examples of ways of working that seem diametrically different to the “Conventional Wisdom”. We have examples where residents are not (effectively) incarcerated, medicalised and infantilised but treated as valuable and integral members of the community.

It might even be that people might really want to “go into care”. To go to a place where they are helped, supported and encouraged to be active members and even re-engage with community – a paradigmatic shift not unconnected with the changes happening in the workplace – where there are companies where people actually want to work – and not just for money.

Of course architecture is key, and maybe that isn’t always obvious, but without the right attitude it will at best be just an improvement. We need both.

Thank you opening my eyes to yet more positive possibilities.

Thanks so much, William, for your comprehensive response. Your research has given you good insight into Teal organizations.

My biggest “Aha” experience came from Frederic Laloux’s “Reinventing Organizations.” But my journey began more than 30 years ago when a member of a client group challenged me to design a nursing home with ‘no corridors.’ As a nurse she saw corridors as institutional. Looking back, that was my ‘first big step for elderkind.’ That led to my first household project in the 1990s. When I saw its success in terms of happier residents and a 2/3 reduction in use of suppressants, I became an advocate for the household model.

“Reinventing Organizations” got me excited about teal organizations and so I began investigating the possibility of taking the household model Teal. Whereas I previously wanted to see long-term care separated from healthcare (LTC is only about 20% medical), I now feel, as you do, that the healthcare sector as a whole, including long-term care and home care, is in great need. Change is not enough, however. It needs to be reinvented.

Brian Robertson, the developer of the Holacracy organizational approach, states that “it is not simply a bolt-on technique that you add on top of your existing structure, but a fundamental shift in the way power works and the way a company is organized.”

Reinventing healthcare is a real challenge. It’s culture is so entrenched. Dr. Margaret Hannah, in “Humanising Healthcare” talks about the “clinical gaze” and doctors viewing the human body as a machine, to be fixed at all costs. But she also describes new transformative practices taking hold. Dr. Victoria Sweet, author of “God’s Hotel,” confirms that the human body is viewed by most doctors as a machine to be fixed, while she compares it to a plant, that has the ability to heal itself.

Yes, architecture is important. The built environment plays a significant role. However, in healthcare the way the care is delivered is as important. For example, the household model is only successful if the care is provided by self-managed teams of caregivers dedicated to each household. Both are required.

Thank you, William, for your insights. Welcome aboard this exciting journey for change. Changing the healthcare sector is the appropriate mission for you and I. Other sectors will attract others. There are enough challenges to go around. What’s important is that each one of us align ourselves with what attracts our interest and gives us joy.

Rudy

Since this article was published, there have been further developments in long-term care. Residents are being reconnected with their communities in meaningful ways. The most promising example of long-term care going next-stage is Buurtwonen, the recently created housing arm of Buurtzorg. This combines the very successful homecare model with facilities providing long-term living accommodation and other community needs. For more information see: https://network.aia.org/designforaging/blogs/isabella-rosse/2016/10/24/bringing-long-term-care-back-into-community