By Anna Betz for Enlivening Edge

Part 1 of a 3-part interview series

Buurtzorg as a new organisational healthcare model and Jos de Blok as its inspirational leader have become a symbol for transformation in health and social care and an inspiration to people in many places around the world including the UK.

Jos has started to work with over 10 National Health Service organisations in the UK and supports 4 pilot projects in London in collaboration with Public World. He is hoping to show how results, in the UK too, can be different both in quality and quantity when the primary focus in health and social care is on building trusting relationships.

I decided to interview Jos about his own journey and that of Buurtzorg since more and more people and organisations feel the tension he felt and responded to in 2005 when he got together with a small group of friends and colleagues and started laying the foundations for what was to become Buurtzorg.

I decided to interview Jos about his own journey and that of Buurtzorg since more and more people and organisations feel the tension he felt and responded to in 2005 when he got together with a small group of friends and colleagues and started laying the foundations for what was to become Buurtzorg.

Buurtzorg is an example of how ‘A cohesive group with strong trust and a clear sense of collective purpose can move mountains.’ Evolutionary Entrepreneurship: Engaging Collective Will, by Helen Titchen Beeth

Anna: What in your personal life prepared you for the journey leading to Buurtzorg?

Jos: There are different things that motivated me. My heart is in nursing and I was very motivated to show what could be done differently with much better results. I had the experience of 25 years on one hand as a professional nurse and on the other hand as a managing director. In the 80’s I worked as a district nurse and experienced how community health nursing could be done which in fact was quite similar to what we are now doing with Buurtzorg.

There were no hierarchies in the 80’s. We had quite autonomous teams working in the villages and in the cities. Then in the late 90’s I became manager of a homecare organisation. I saw that the way homecare was organized made it more and more difficult for nurses to do their work. The management structure lead to a lot of bureaucracy, worse care, and a lot of fragmentation.

I got more and more frustrated when I saw how a lot of patients clearly suffered from the way we organized things. People around me were managing their nurses and their homecare workers but not really enabling them to open up to new learning experiences. Because I knew from my experience how it could be done better, I did what I thought was better to do: decided to quit the job as a homecare managing director, and started this initiative.

Anna: What was the tension or question to which your work became the answer?

Jos: The tension I carried in me was the experience of how it could be for nurses and patients and how it wasn’t as I continued to work in the service.

Buurtzorg became the answer to my tension and the question I carried in me.

After resigning from what was a good job with a good salary, I had a lot of uncertainties. The resigning gave me a lot of freedom, freedom in my mind, knowing I could just do what was better and what was the right thing to do.

Anna: Did you have any fears of survival after giving up a secure job?

Jos: We only had small savings. My wife and I resigned together which made it a double risk with 5 children between ages 12 and 21. I worked as a consultant advising organisations who were interested in the concept. This provided our main income. Working as an organisational consultant allowed me to have enough time to prepare our own foundation.

I knew what necessary conditions we needed to create to start our own organization. We took all these risks because we thought there are some different ways to earn some money and we were quite sure that we could manage. My feeling was that if it didn’t work, I would just find another job.

However, from the moment we resigned we had a real feeling that this would be successful and we could manage. We didn’t need too much as we avoided a lot of costs in the first year.

Because of my experience in the organisations I worked at before, I was convinced that the results of working in this way would be much better in terms of quality but also financially for people and payment systems. So I had a strong feeling myself and had it confirmed by a lot of people who thought that this was a good thing to do. I talked with a lot of people with different expertise, people who had a long history in healthcare but also people who were financial experts. And every time we thought “Oh yes, this could be done, someone has to start it,” and a lot of people said that if we started it they would contribute. We didn’t meet people who said that this was a really bad idea.

Anna: What were some important considerations and how long did it take from the first idea to it becoming a reality?

Jos: We met with some friends in 2005 and in the beginning of 2006 and had a lot of evenings where we talked about this. We described in detail what we thought had to be done, what our vision was and how to deal with patients, but also how to work in this way. Again and again I wrote down my thoughts on that, and then I accepted that people recognized these things and thought it was consistent and altogether a good concept.

From the start I considered different perspectives to make it work, the healthcare perspective but also the organisational dynamics and the financial perspective.

It certainly was not just a simple idea but it was really thought through and discussed with a lot of people. When we started it was quite clear what we wanted to do, what was needed to reach our aims and what kind of process we needed to develop and let it flow.

The idea about good healthcare was that it should connect to the intrinsic motivation of the nurses, that it had to be inspiring to do this work so that the nurses themselves would be the carriers of the vision and the concepts.

Anna: Would you say that the organisational structures you developed enabled the vision of better healthcare to be realized in the marketplace?

Jos: The structures are designed such that the way of working empowers workers as well as patients. When I worked as a nurse, I was intrigued how ‘empowering people’ looked in practice. You need to have the right attitude and the right competences. I learnt a lot from experienced colleagues and then tried to solve problems in different ways while delivering activities. We can take care of people in different ways. For example, I can be task-oriented and say “Ok I come to help you with showering or do some more other supportive tasks.”

What I wanted to show was that if you focus on the relation, build a trusting relationship and you are a good nurse you can help people to feel empowered.

However, for this to be possible, you need to have the autonomy to make your own decisions. The same applies when working in an environment with colleagues and you want to create something new. Working in a supportive environment will lead to different results and feel more empowering for yourself as a nurse.

I was convinced that you needed a flat organization. You need a network of people who work together, share the same values and feel responsible for organising all the things that are necessary. That leads to a completely different dynamic from when you work in a hierarchical culture.

Anna: Did you have connections in the public or the private sector that supported your vision?

Jos: In the beginning we didn’t have many contacts, but we had a lot of attention from all kinds of people from the very start. We also knew that there were a lot of people who we didn’t know but who were quite supportive. Later I heard that some influential people had been supporting our ideas early on. They saw that we went for a kind of system change and a breakthrough in systems which was necessary.

So from 2007, we got support from a government minister. She came to visit us and from that moment we built quite an intensive relationship with her. She asked me to come to the Hague and talk with her about these things, and talk with the people in the ministry about our ideas.

Anna: So you started in late 2005 and early 2006 with friends. When was it that the government or ministries became really supportive?

Jos: That was in 2007. At that time we had 3 locations, and in May or June we were on television for the first time. One of the political parties said ‘We want to make a report’ and after that in August 2007 the minister of health joined one of our nurses in the teams in the neighbourhood. Together with a nurse he went to visit patients, which was followed by a roundtable meeting with various ministers and nurses.

Nurses talked about their feelings, their profession, the difference between the way they worked before and how they work now. As ministers they were actually very authentic. They understood very well what the difference was and how nurses were struggling in the old system and how they could just do the right things in this new environment.

Anna: What governance and decision-making models do you use in Buurtzorg?

Jos: The way things are working is based on some logical guidelines. So we say in community healthcare, there will be the daily routines based on the care for the patients. These routines are quite logical. Of course the way things work out can be a little bit different but they are based on the standards of good quality care. Our aim is to deliver the best possible care. So we have to define what that is.

In decision-making we choose the consensus model. Everyone in the team has to agree with a certain decision. Of course there have been some challenges.

In decision-making we choose the consensus model. Everyone in the team has to agree with a certain decision. Of course there have been some challenges.

We learnt a lot of things and developed trainings. I worked together with some friends who did coaching, and I ran a coaching agency myself. Based on our experience, we wrote articles on our web about topics that came up. For example, how to deal with conflict, how to have an effective meeting, or how to divide roles.

Every time when there were some issues, we thought it would be good to talk about them, and we wrote an article about it. It also meant that every team, whether they were just starting as a new team or already had been running, could have a training on the different topics that came up for them as a team. At that point, we developed two half-day trainings.

Anna: Did that training help to bring everyone to a similar level of understanding and make consensus-based decision-making more effective?

Jos: That was one of our struggles. There were teams who did have that problem, and there were teams who had a good and effective way to work with consensus. Teams who struggled with it were advised to have a training on decision-making, for example.

Whenever you meet a challenge or problem, this is an opportunity to learn and find out how to deal with it. Maybe you need to book a training or coaching session or both.

The key is that training or coaching should be available as and when you need it. The central organisation always supported teams and individuals to book training and coaching sessions as and when they needed them. The development of the role of the coach was very important in that. By the end of 2007, we had our first coaches who were always available when a team or individual was struggling. We always advise everyone to ask for support, and coaches would always offer whatever kind of support was needed. We didn’t have guidelines or structures to say “When you have this, you should do this.”

Anna: Do you have performance indicators or improvement measures? How do you prove to the government or those who pay you, that your work is good?

Jos: What the government or others asked for didn’t deal so much with the performance.

You need to have a quality system and satisfaction research with patients. That was more or less it. What we said to them was, we’ve got to give you more information than you are asking for.

You need to have a quality system and satisfaction research with patients. That was more or less it. What we said to them was, we’ve got to give you more information than you are asking for.

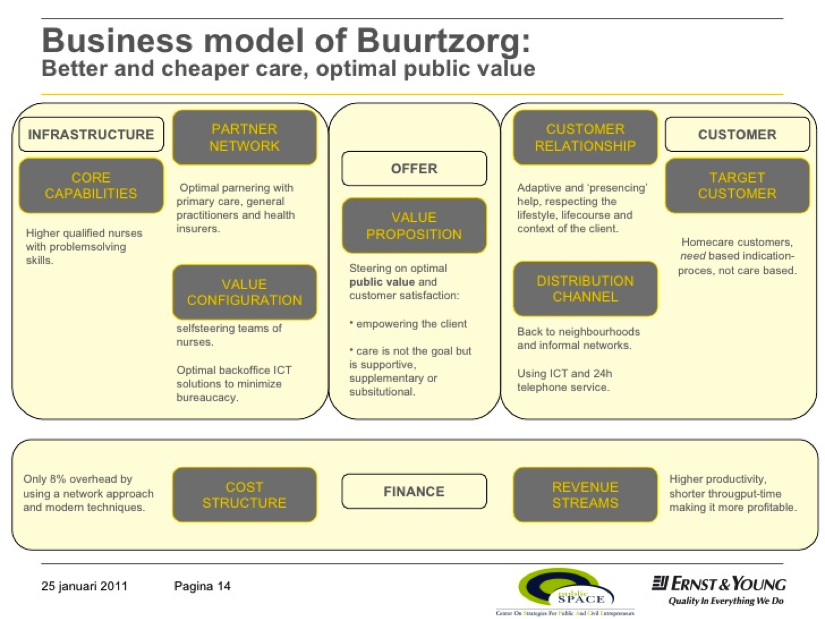

We want to show what we are doing so far and how it affects both nurses and patients. We were supported by the government because Ernst & Young in 2009 and later KPMG in 2014 were asked to measure the differences between Buurtzorg and other organisations.

They made a social business case. It had quite an impact because it showed there could be savings of hundreds of millions of euros by working this way. We also did some other research conducted by MIVEL (2008) that was more focused on satisfaction of patients and doctors.. It compared Buurtzorg with 300 other organisations. We had high satisfaction rates of the company. MIVEL is an institute that does a lot of research in primary healthcare. We thought if we asked other institutions to do research, and they are showing that we are doing much better, then we have a strong position in the discussion.

When we started, a lot of people were very cynical because we did a lot things different from how other organisations worked and what people were used to. For example, we worked with higher-educated nurses. A lot of other people told us that they would be much too expensive to do this simple work. We had to explain a lot and not become defensive. The idea was to show our work and invite researchers to join our team on visits, see what we are doing and then let them give their opinion of that.

Anna: Who contracted and funded the research?

Jos: Each situation was different. The first research, which was during a whole transition programme, was paid by the government. A lot of other organisations took part in this transition programme. We were paid some extra money for that.

Another piece of research was focused on outcome and cost and was more of a financial kind of report which was done by Ernst & Young. This second research was paid by the health insurers and also partly by us. So we were partners in this research. The last research in 2014 was paid for by the government.

Anna: Once you retire what will happen? Does Buurtzorg have a constitution to ensure its vision and principles of organizing continue?

Jos: My idea is that these patterns of working now are almost becoming mainstream in Holland. The payment system is changing, the discussion is how healthcare should be influenced by what we are doing. So I think the environment is changing, and it is supportive to this way of working. So the conditions are much better now than when we started. It is asking all these things from professionals; discussions about self-organising and self-organising teams are happening everywhere .

I just read an article this morning which said that 50% of all the healthcare organisations are focusing on self-organisation now. When we started we were the only one. So this is a development which is very strong.

This movement which includes agile thinking is very strong. I think the principles are central, and the foundation of Buurtzorg is very strong. So we are very sustainable also when I am not there. They are less and less dependent on me.

Anna: Do you trust that the developments have become so much part of people’s inner operating system that they will continue because it is an improvement on what came before?

Jos: Yes, it feels very natural for people now to work in this way. Monday evening I was in Utrecht. We had a meeting with nurses who applied for the job. There were a lot of nurses from different teams there talking about their work and Buurtzorg. I was just listening. The way they talked about their work, the way they said that it is so normal and so natural to do it this way, gave me such a good feeling. It really made my day.

It is funny to see the nurses now that have been working for Buurztorg for 5, 6 or 7 years. For a lot of them, working with very vulnerable patients in challenging home situations can sometimes be difficult to handle. They were explaining this to the new nurses who wanted to come and work for Buurtzorg. The new nurses got so excited because they were still struggling with all kinds of rules and regulations which were bothering them in their daily work.

When I hear continuously how our nurses talk about their logic of how it is to work this way, I have quite a good feeling about what would happen when I am not in this position anymore.

Anna: We talked about the self-organisation of the nurses. What about the self-care and the self-management of citizens and patients? What is their role in relation to the work of Buurtzorg?

Jos: What I see is some kind of process when you invite people to participate in supporting vulnerable citizens, and you create routines for that and it becomes a pattern. That is when it becomes the new normal. So we intentionally invite family members to take part in the process. Then we think from a positive perspective that people want to do something for each other. When they are supported in how to do it, it helps both sides. So the support has more of a social context.

As professionals, nurses may have some difference in values and knowledge of course, but they always depend to some degree on the informal network in the community. When as a nurse you are supported by volunteers or informal carers, you build another relationship with them which is different from the relationship with other professionals. We said we wanted to have a good mix between formal and informal care to be integrated in the daily routines of professionals. Professionals see themselves as part of the community. and also think it very normal to invite people and be invited for a conversation, into people’s homes, to meetings in the community, etc.

If you enjoyed this 1st part of the interview and want to learn more about the Buurtzorg journey, click here to get to part 2.

Anna’s background is in Health and Socialcare with training in Herbal Medicine, Socialwork, Mindfulness Practice, Transparent Communication, and Systemic Family Therapy. She practices a proactive evolutionary approach to Health and Wellbeing and leads on projects in the UK National Health Serive using Mindfulness and diet for people suffering from chronic inflammatory diseases like diabetes and dementia. Her passion for building thriving and sustainable communities inspired her to co-found the HealthCommonsHub. She feels at home in places where individual, communal, organisational, and social evolution meet, and where people support each other in becoming whole and feel enlivened.

Anna’s background is in Health and Socialcare with training in Herbal Medicine, Socialwork, Mindfulness Practice, Transparent Communication, and Systemic Family Therapy. She practices a proactive evolutionary approach to Health and Wellbeing and leads on projects in the UK National Health Serive using Mindfulness and diet for people suffering from chronic inflammatory diseases like diabetes and dementia. Her passion for building thriving and sustainable communities inspired her to co-found the HealthCommonsHub. She feels at home in places where individual, communal, organisational, and social evolution meet, and where people support each other in becoming whole and feel enlivened.